By Patricia Dolor

Trigger Warning: This article mentions suicide.

The letter hidden in her backpack had a paragraph for every person in her life: her sister, her brother, her mom, her dad. The act was fully planned; 15-year-old Karandeep Gill was going to take her life. During math class, she went to the washroom and took a bottle of pills that were prescribed to her for anxiety – this was it. This was going to be the moment where all her pain would vanish, her worries would disappear, and she thought to herself, “I finally won’t be a burden to anybody around me.”

Then, suddenly, came the regret. Gill broke down and brought herself to the school’s office, where she said she had done something horrible. An ambulance rushed her to the hospital.

When Gill had her first panic attack at 14 years old, she knew something was wrong, describing to her sister that it felt like she was having a heart attack. Soon after, came a wave of depression – making mundane tasks hard to do, making living a chore that was too difficult to carry on doing. Suicide was always in the back of Gill’s mind, but now she began to plan her own death.

One of her hospitalizations changed her life. Gill was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type and received a medication that helped her mind switch from restless to peaceful.

“Surviving from the suicide attempt didn’t just make me alive physically, it allowed me to survive mentally because I always think about the regret I had after swallowing those pills, because I never thought of attempting suicide again,” Gill says. Even after being named Canada’s 2020 Faces of Mental Illness, dealing with mental illness continues to be a challenge for Gill. It’s the good days, the ones where she wants to be alive, that she says keep her going.

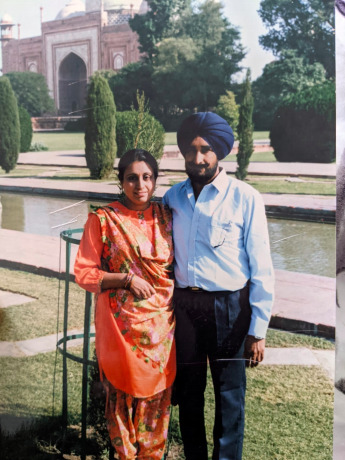

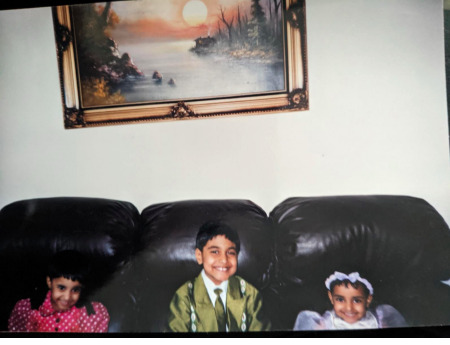

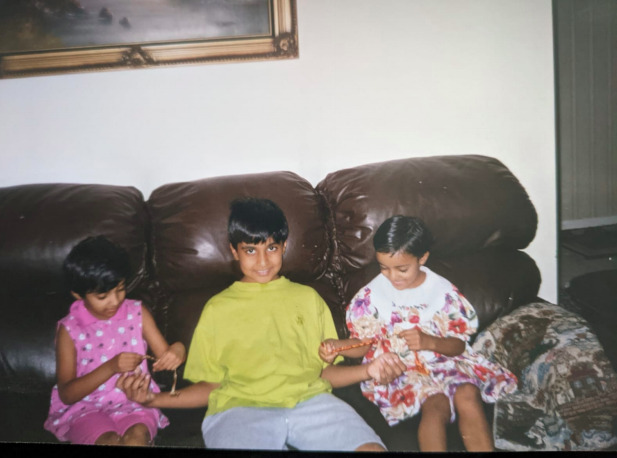

Gill, who is 25 years old now, comes from an immigrant family from Punjab, India. Gill’s mother immigrated to Canada at 20 years old and had to work multiple jobs to survive as a new immigrant. She did everything she could to start a new life for her family.

In India, mental illness was taboo, even though it has the highest suicide rate in South-East Asia, according to a report done by the World Health Organization.

“I don’t think she believed in mental illness,” Gill says in describing how her mother reacted to her struggles as a teen. “She would say, ‘This never happened in India when I was growing up. If this was happening to us as kids, no one would take us seriously. They would just tell us to push ourselves and to force ourselves to get up.’”

When Gill was first hospitalized, she knows it was difficult for her mother. Gill couldn’t comprehend what was happening either. While she was in the hospital, her mother was hesitant to tell people that the hospitalization was for a mental health reason, and tried to say any physical problem that she could think of. “I remember someone calling my mom and saying, ‘She’s just attention-seeking, she just wants attention,’ and that kind of broke me because nobody wants to suffer every day, mentally or physically, on purpose.”

Mental illness took over Gill’s life. From 2010-2014, she was hospitalized seven times. Her family still couldn’t understand, because in their minds, they thought that she was too young to have anything to stress about. Her family couldn’t see the chemical imbalance in her brain that was triggering her depressive episodes and the frightening hallucinations she was beginning to experience.

Marie Remy lost her sister Fabiola to mental illness and vowed to change the outcome for other families. She is the founder of Fabiola’s Addiction and Mental Health Awareness & Support Foundation and she launched the foundation on Nov. 30, 2018 to commemorate Fabiola’s 36th birthday.

“After my sister’s passing, I had these moments where I thought about how things could have turned out differently, and I realized how little I understood about what my sister was going through. With my husband and my niece, we started talking about how a lack of awareness about mental health and addiction was an issue in our communities, and we wanted to change that,” Remy says.

Remy comes from an immigrant family and understands the struggle and connection between mental illness and immigrant families all too well.

The taboo in immigrant communities, Remy says, stems from stigma. “Many people regard mental illness as a sign of weakness. There’s also that comparison that someone else had it worse in many families, so you need to tough it out. There is also the sense of shame that many associate with mental illness. We don’t want others to know someone in our family has a mental illness, so we will not treat it as such.”

Immigrant families move to a foreign country to search for a better life, sometimes not considering how this will affect their children emotionally or mentally. The silence about mental health affects how children of immigrants are being raised because it is not being addressed the same way other illnesses are being talked about, Remy says.

“Mental illness is not something we can wish or pray away. We may think we are protecting our children and our family by keeping these things a family secret, but in reality, we are letting our children suffer in silence.”

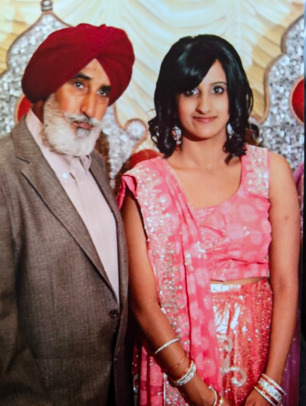

Gill went back to the hospital in 2020. She started to experience visual hallucinations, a surreal feeling of not being able to decipher what is there and what is not, that are triggered by stressful moments in her life. A fairly new feeling, Gill tried her best to cope with the hallucinations. She learned how to stay grounded, and how to try her best to keep herself in the present moment, sometimes through touching something near and real, such as a desk. Gill also tried out a strategy where she thinks about memorable moments that sparked positive emotions in her life, especially the ones she shared with her late father, to bring her back to reality.

That same year, a pharmacist showed Gill and her mother a computerized image of what happens to the brain after every psychotic episode. Mental illness isn’t something tangible, you can’t see or touch it, but when that physical representation was presented, it made not just Gill’s mother understand but Gill herself believe and accept it more. Gill’s mother recognized that her daughter’s condition is a brain imbalance that can be controlled with medications.

After the hospitalization, Gill attended an intensive out-patient program where she gained understanding about coping strategies, the effects of her medications, and learned how to challenge negative thoughts that trigger mental instability. She credits the program for her ongoing recovery.

Soon after, Gill became one of Canada’s 2020 Face of Mental Illness. It was a regular day on a sunny summer day in June, scrolling through Instagram, when she saw a “Bell Let’s Talk Day” ad. She clicked the link and decided to apply to become one of the faces. She spoke about her mental health advocacy, her illness, her recovery process and her goals. Hundreds of people applied and within different rounds of interviews, she got a call that she will be one of the faces to represent the one in five Canadians affected by mental illness.

Gill’s mental health advocacy started in her last year of high school. She decided to share her experience when one of her teachers invited her to speak at a “special development” day where teachers learn more about mental health. Gill’s teacher, who stood by her side throughout her recovery journey, said that Gill will help other students by sharing her story, and also help the teachers understand the struggles a student may be facing.

Gill sharing her struggles and her recovery immediately caught the attention of a representative for the Mental Health Commission of Canada. Afterwards, she was asked to share her story in other high schools.

“My primary reason for sharing my story and going public with it is because I used to listen to other people’s stories on a regular basis, to be inspired to keep going and learning about their recovery process, their illness and seeing the similarities with my own mental illness. I wanted to be the figure for somebody else. I realize that what I’m going through is for a reason and that is that mental illness can’t end your life,” Gill says.

Gill also helps out in a local group called SOCH – meaning “a thought” in Hindi, Urdu and Punjabi. The organization promotes mental health awareness in the South Asian community. She hosted workshops, such as one on schizophrenia. This organization has helped her connect with people globally, including a woman in the U.S who is publishing a book, and is dedicating two chapters to Gill’s story.

Gill is exercising every day, eating healthy, studying honours speech communication and business at the University of Waterloo, and hopes to publish her own book. She is also planning to launch a self-care company called Living in Peace, where she will sell items that help with mental health, such as face masks and simplistic hygiene sets for days where it gets hard to do simple tasks.

Gill reflects on that 15-year-old girl who thought all her misery would end if she took her life.

“I know now that I deserve to be in this world, that I deserve, fully, to be alive.”