By Ruth Young

Walking up the steps and through the silver rhino-branded awning into the bar Woody’s on a busy Saturday night can feel overwhelming. You push and swerve through crowds until you reach a small set of stairs to a sunken landing centered around a small wooden stage with a bright pink sequin curtain backdrop. There, Toronto drag queens can be found lip-syncing, dancing and flipping their wigs. They are wearing holographic vibrant outfits stuffed with padded hips and breasts; drawn on eyebrows and dark eye shadow.

Fast forward to June 2020 and the Toronto drag queen Sofonda Cox is putting on make-up and fastening her wig in a friend’s North York spare bathroom. Dressed in a reflective bodysuit, she steps out onto a hot cement driveway to Beyoncé’s “Crazy in Love” in front of a small crowd of neighbours both young and old standing six feet apart and donning masks.

The pandemic has stripped Toronto’s drag queens of their traditional performing venues in and around the Church and Wellesley village and the people who filled them. Some queens have traded those venues for virtual ones and others have stepped back from drag entirely.

Before the pandemic shuttered businesses and restaurants stacked their tables and chairs for takeout and delivery lines, walking through the village’s rainbow flagged streets felt like the opening scene of “Beauty and the Beast” with passersby saying ‘Hello’ to each other, says Justin Gray, who goes by the name Fisher Price on stage.

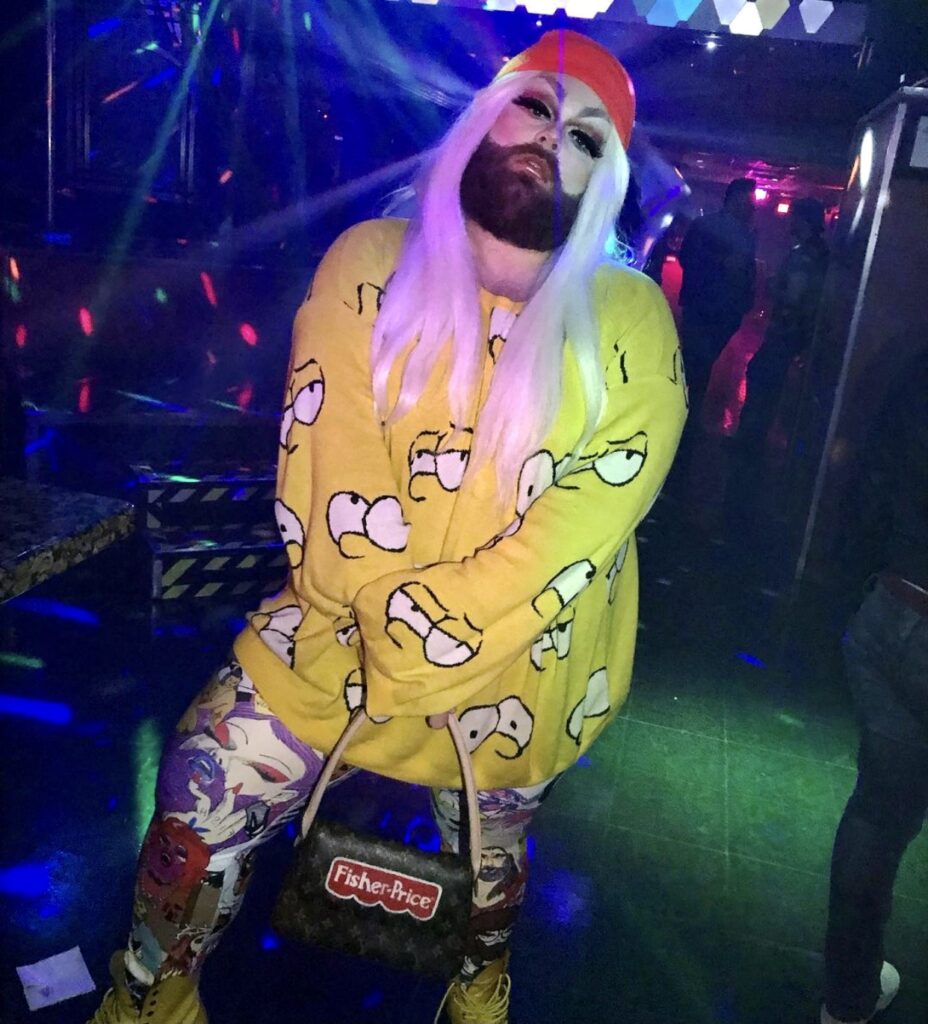

By day, Gray works in television and is the creator and writer behind CBC Gem’s “Queens.” Prior to the pandemic, Gray could be found at The Beaver, conceptualizing and organizing monthly themed events. One of the most memorable being his drag tribute to Meryl Streep. Dressed as a bearded Julia Childs from the film “Julie & Julia,” Fisher Price took the stage with a raw chicken on his fist and the ‘La La La’s’ of the Spice Girls’ “Spice up your Life” playing in the background.

“People were silent and then someone screamed from the back of the bar, ‘Oh f— yeah!’ and then there was just the most obnoxious applause,” says Gray. After his performance, Gray walked over to the bar, chicken in hand, as the crowd parted and cleared a path. Justin threw the fowl in the garbage, cleaned himself off, grabbed a drink and joined the crowd.

Drag shows for the performers are more than just a hobby or a reason to dress up.

“I’m a temptress and the art of drag is all of that,” says Jason Pelletier, who is also known as the drag queen Jezebel Bardot. “You’re fooling people to see something that’s really not true. I’m the boy dressed up as a sexy woman, but I want for three minutes — when I’m not talking and I’m lip syncing and I’m dressed up — to transport you into something and make you believe something that’s not fully true.”

For some, drag is also an integral part of accepting queer identity. For Pelletier, drag offers the chance “to embrace femininity” for many cisgendered queer men “who have kinda stifled and been embarrassed of their femininity for so long.”

The symbols that differentiate this neighbourhood from others like the bright blue building covered in spray painted faces and branded with the Crews and Tangos logo and the rainbow crosswalk at the intersection of Church and Wellesley are still standing. But the people who gave life to these buildings and whose shoes clicked and clacked and thumped across the street are missing.

Corner of Church Street and Maitland Street on April 9th 2021 (Ruth Young/T.)

Corner of Church Street and Maitland Street on April 9th 2021 (Ruth Young/T.) Front entrance of Crews & Tangos on April 9th 2021 (Ruth Young/T.)

Front entrance of Crews & Tangos on April 9th 2021 (Ruth Young/T.) Rainbow sidewalk at the corner of Church Street and Alexander Street on April 9th 2021 (Ruth Young/T.)

Rainbow sidewalk at the corner of Church Street and Alexander Street on April 9th 2021 (Ruth Young/T.) Entrance of Flash on April 9th 2021 (Ruth Young/T.)

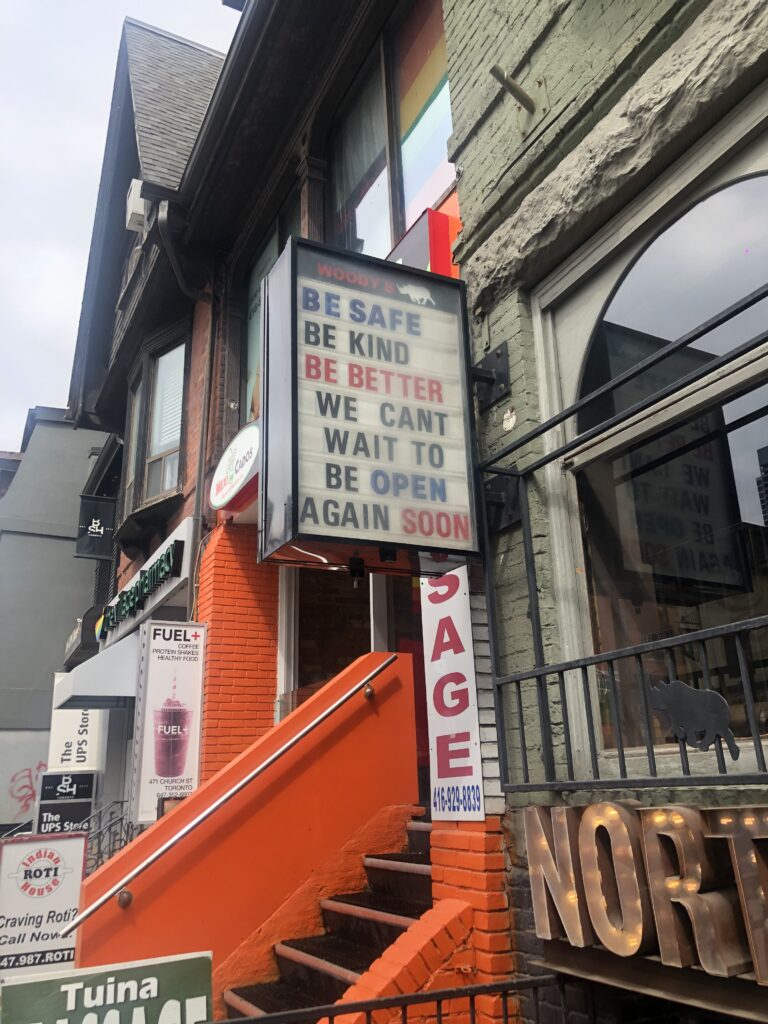

Entrance of Flash on April 9th 2021 (Ruth Young/T.) Sign outside of Woody’s on April 9th 2021 (Ruth Young/T.)

Sign outside of Woody’s on April 9th 2021 (Ruth Young/T.)

The closure of these queer spaces has also left some drag queen performers feeling forgotten. Gray believes those in his community have not been looked after throughout the pandemic. “In the grand scheme of things, to the government you’re kinda deemed impractical, more of a decorative piece of culture opposed to a legitimate part of history,” he says.

Community members of the Church and Wellesley area have stepped in to offer support. The Glad Day Bookstore started an emergency relief fund the day after the shutdown in March 2020 to help LGBTQ2S artists, performers and tip-based workers.

“Queer and trans communities have always provided mutual aid because they can’t depend on the government to support their most marginalized members,” says Tianna Henry, community outreach and event director at Glad Day.

Prior to the pandemic, Gray notes how he was always busy either securing a gig or preparing for one. Stepping away from drag over the last year gave him the time to reflect. “When you finally sit down and take a look at yourself, a lot of us are very proud and very beloved to the body of work we’ve created,” says Gray. “But what’s deemed a worthwhile art to give funding to, to support during a pandemic?”

In answering this question, Gray commented on the fear some drag queen performers felt. “People were freaking out because they lost their weekly gigs and they weren’t making money,” he says. “[They were] left feeling, ‘You love us every June, you love to talk about us every June, why don’t you love us in this regard all year round?’”

In Toronto, one municipal relief program was available to artists, the TOArtist COVID-19 Response Fund. This program offered financial aid to individual artists, the majority of which were from the music industry.

With bars and nightclubs closed, the venues for some to express these parts of themselves have changed to driveways and screens. Sofonda Cox hosts her “Sofonday” event through Instagram Live. In front of a crafted leopard print backdrop, she lip syncs to a variety of classic drag show songs like a remix of RuPaul’s “Covergirl.” Her movements are confined to the small space her camera will catch and the cheering applause she used to hear is now in the form of comments and emojis popping up on her screen.

With everybody hoping the pandemic and its restrictions will soon be lifted and normal life returns, what this new normal will look like for the village and its community is unclear. For Pelletier, drag and community go hand in hand. Reflecting on his first time in drag, Pelletier says he immediately realized that drag was not just for him, but it was for an entire community. “I was like, ‘Holy crap! Drag is powerful,’” he says.

However, the pandemic has allowed Pelletier to expand his community. “I worked more gigs for little small projects in collaboration with nonbinary queens or drag kings then I have within the last five years.”

Despite the adversity placed on the community from government closures due to the pandemic and financial concerns, Pelletier still clings to hope for the future of drag in the village. Just as the start of the pandemic caused Sofonda Cox to get creative and trade a stage for a driveway or a screen, he is optimistic the village’s strong sense of community will survive. He believes “the people are still connected, we always find a way. We will find a way to resurface. It’s like a phoenix rising.”