By Kuwarjeet Singh Arora

With tall, muscular bodies, long warrior-style beards and nicely wrapped turbans, they walked into the waist-deep water. Mandeep Singh and his group of volunteers had no time to nap after their eight-hour drive from Toronto to Montreal. They started putting down dozens of sandbags to block the floodwater from entering the nearby homes.

Melting ice-cold water began flowing into a local nunnery in the Pierrefonds-Roxboro area in Montreal, and Mandeep and his squad of Khalsa Aid Canada volunteers kept going, their beards frozen, their hands numb, and their feet protected only by soaking wet shoes.

“We can see the situation right away,” remembers Singh, who runs his own capital markets firm in Toronto when he is not leading volunteers at Khalsa aid as he was doing that day in the spring of 2019.

“Homes were flooded up to halfway through the door. We can see half of the neighborhood underwater.”

The volunteers mobilized, lifting bag after bag of sand and rocks weighing in at about 66 pounds each.

“The best way for us to do this is just to build a long chain passing the bags,” Mandeep recalls. “That was it, that became the event of the day right away; all of a sudden we were passing sandbags at a phenomenal rate.”

Their lips were rough from the intense wind, and they headed home with windburns on their faces, but they were making a difference.

Khalsa Aid International is a non-governmental organization that provides humanitarian aid in disaster areas and civil conflict zones around the world. It was established in 1999 in the United Kingdom by Ravinder Singh, who still leads the organization. Canadian operations are headquartered in Victoria, B.C. and there are chapters in 13 locations across Canada, according to Jatinder Singh, National Director for Khalsa Aid Canada. Their motto, stated on the website, is to “Recognize the whole human race as one.” It comes from Guru Gobind Singh, the Tenth Guru of the Sikhs. Anyone can volunteer.

“Our only check is to ensure our key team leaderships have a criminal check that allows them to work with vulnerable groups,” Jatinder says, “A number of our chapters are run by females and we also have a significant number of non-Sikhs who volunteer with us across Canada.”

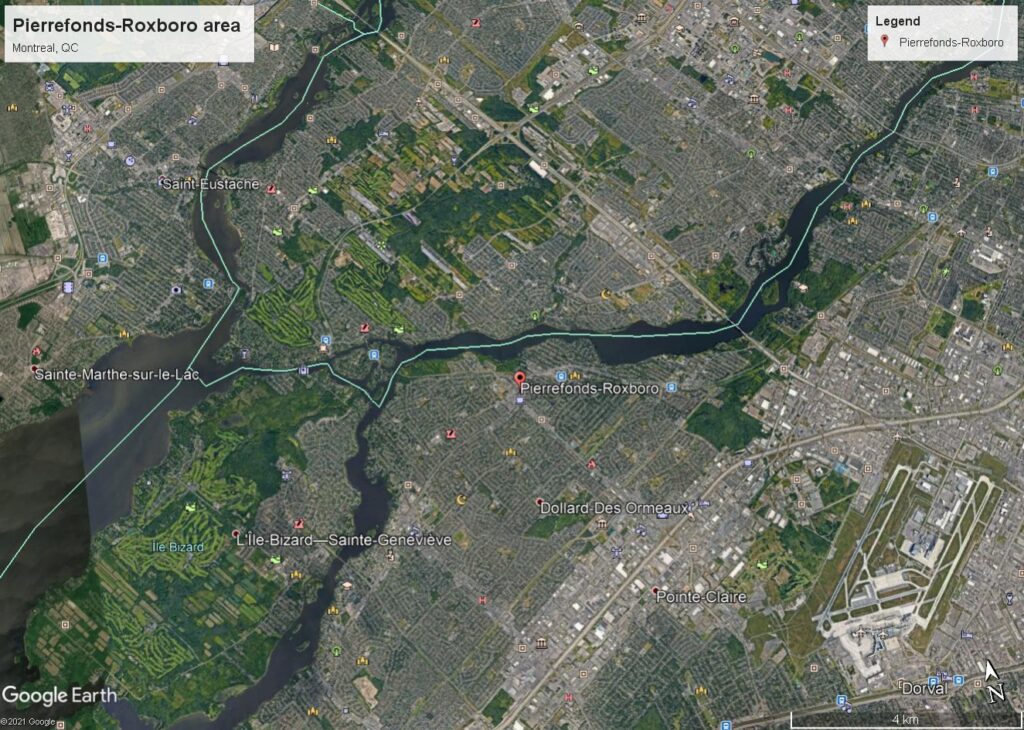

A map that compares before and after when floods hit the Pierrefonds-Roxboro area in Montreal.

Mandeep first volunteered with Khalsa Aid in 2016. The following year, he headed to Quebec when spring snowfall and heavy rains caused rivers to overflow their banks, flooding several communities. He had been in the corporate world for more than a decade, working at the Royal Bank of Canada before opening his own financial firm. He describes his professional life then as fast-paced and high-pressure. Sometimes he was forced to lay off employees.

He spent some of his time organizing charity events such as fundraisers for different social causes, but a day came when he realized working in banking was limiting him from giving back to the community and he was missing the feeling of true service.

Around the same time, he received a chance call from Khalsa Aid Canada stemming from his charity work. He recalls checking out their warehouse and meeting with Kanwar Singh, the nephew of the founder. They talked about the organization’s work helping Syrian refugees in Iraq, and Mandeep got inspired and decided to join as a team leader.

In 2019, when floodwaters again began to rise in Quebec, Mandeep returned. But, during his two-year absence, things had changed. The province had just passed Bill 21, a so-called secularism law that banned public workers from wearing religious symbols.

Most of the Khalsa Aid volunteers wore a turban, and a Kirpan, a dagger that Sikhs wear as a religious symbol to defend the needy. Many were people of color, a rarity among the volunteers helping out during the flood.

Mandeep says they knew they were going to find a different attitude when they arrived in Quebec this time, and would perhaps be viewed with suspicion despite being there to help.

“It didn’t matter what they were going to say to us, it didn’t matter what they were going to think about us,” he said. “We know what they’re going to think, but that doesn’t mean we can’t go and serve them anyways.”

Mandeep and some of the men he volunteered with recall arriving at one house where the rising water was already waist-high in the basement. Although they were there to try to save the property, the homeowner’s greeting was far from friendly. Before they could get to work, he pointed at one volunteer’s turban and questioned their ability to help him. His tone was rude and remained that way even when the volunteers jumped into the water that got deeper with each step down to his basement.

It took the volunteers 15 or 20 minutes to get the job done, bucket by bucket. When they were done bailing out the basement and had begun stacking sandbags around the house, they noticed the homeowner was recording their efforts on his phone.

As he did so, they can remember him saying: “By the grace of God, angels were sent to defend our homes.”

The work was grueling. By mid-afternoon, the water was going inside of the lining of the volunteers’ jackets, but they didn’t stop. Shifts were 16 to 17 hours long, with only small food breaks.

At the end of that first shift, the mayor’s office called Mandeep to recognize the humanitarian service they had provided to the city. After that, they joined forces with Team Rubicon Canada, a team of military veterans with first responders to disaster-affected communities, and the volunteers from Newfoundland and Quebec fire department at the frontlines.

Mandeep says that as homes and shops were saved, distrust among the locals melted away and they started to embrace the volunteers.

He describes the changing attitudes this way: “The people who were supposed to be terrorists are no longer terrorists, they’re now supporters of the community.”

(Kuwarjeet Singh Arora/T•)

These days, the Khalsa Aid Canada volunteers have turned their attention to helping people who are homeless people and those who struggle with addictions. Jatinder says these efforts include distributing groceries, warm meals, hygiene products and back-to-school supplies. In Brampton, Ont., the organization serves food to about 50 needy families each day.

“Since March 2020 we’ve been doing the grocery deliveries and grocery availability for anyone that’s in need because of the pandemic. We’ve been packing groceries and distributing groceries for free,” said Jasmail Singh, a community volunteer in the Ontario chapter of Khalsa Aid Canada who was making grocery packages at one of the warehouses in Brampton Ont.

“We sent at least a hundred pound of groceries to Nova Scotia… so anywhere there is a disaster we will help whether it’s here in Toronto, Montreal or Thunder Bay we will see what we can do to help.”

Mandeep, sitting on a chair inside the spacious warehouse where Jasmail is packing up groceries, looks at the other volunteers and thinks about the mission, still reflecting on the experience in Quebec.

He sits up straight and crosses his legs and says: “We asked them, you tell us what is your greatest need and we’ll serve.”