By Lillie Coussee

In 2018, Pat Briffa left her house in the east end of Toronto to go to a doctor’s appointment. She knew the area well, having raised her two daughters there. She got in her car for the route she had taken many times before and turned the radio on, listening to whatever was playing as she loved music tremendously. An easy drive, one would say.

Still, Pat somehow managed to get lost on the way to the doctor, and drove home instead, putting the incident behind her.

Feeling embarrassed, she never told her daughter, Charlotte Briffa, the real reason she didn’t make it to the appointment. But Charlotte knew something was wrong when the receptionist called her later that afternoon saying her mother had never arrived.

Although Charlotte saw signs of dementia earlier that year, she didn’t realize how bad it had gotten. This incident prompted her and her sister to get a formal diagnosis for their mother.

“Dementia affects everything because it affects your brain and your brain tells your body what to do,” she said. “Most notably when she’s tired, she just shuts down and doesn’t know what to do.”

Beyond memory loss, dementia also affects physical abilities such as balance and mobility, makes easy tasks such as preparing a sandwich difficult, impedes the expression of thought and communication, and causes rapid mood swings and confusion, according to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

Pat began having trouble walking and communicating, but her passion for the arts never wavered. In 2020, just before the COVID-19 pandemic, Charlotte came across a program called The Bitove Method, a non-profit arts-based program that aims to improve the lives of older adults living with memory loss and knew her mother would be interested.

The program began 10 years ago when the Bitove family — the same family tied to businessman John Bitove who famously founded the Toronto Raptors — and various Ontario University researchers specializing in culture change in long-term care facilities wanted to create something different than anything else Toronto had seen before when it came to caring for older adults.

Various kinds of medications and therapies exist to treat dementia; however, at Bitove, the purpose is not to treat participants, but rather to build relationships with them and accompany them on their journey, said Katia Engell, the current director of strategy and innovation at Bitove.

Engell, whose grandmother had Alzheimer’s, said she loved creating art and decided to volunteer at Bitove while completing her bachelor’s degree in design at the Ontario College of Art and Design.

Engell fell in love with the community and its members and said it was one of the first places she could be herself.

“I felt so enriched by the relationships I was building with everybody because what other contexts would I be making friends with so many people with so many life experiences as a 20-year-old? It really gave me so much,” she said.

Engell went back to school to get her Master’s of Arts in Recreation and Leisure Studies where she was introduced to relationship-centred care. Bitove is based on this method of caring by building trust and relationships with their participants as well as fostering relationships with care partners and family, but also with music, art, or however else they choose to express themselves.

Many care facilities are oriented around a biomedical theory of care and less so, the social or psychological aspects, treating the person as a body instead of having all these parts, Engell said.

“It’s very alienating. It’s very dehumanizing. It’s very objectifying and people don’t end up getting very good treatment because of that,” she said.

Engell runs the Bitove program on Thursday afternoons, with the help of Susee Padias, the program facilitator, and a member of their artist team. Participants are welcomed into The Canadian Macedonian Place, an apartment complex for retirees in East York and a temporary space for Bitove after the pandemic forced their previous space to close down.

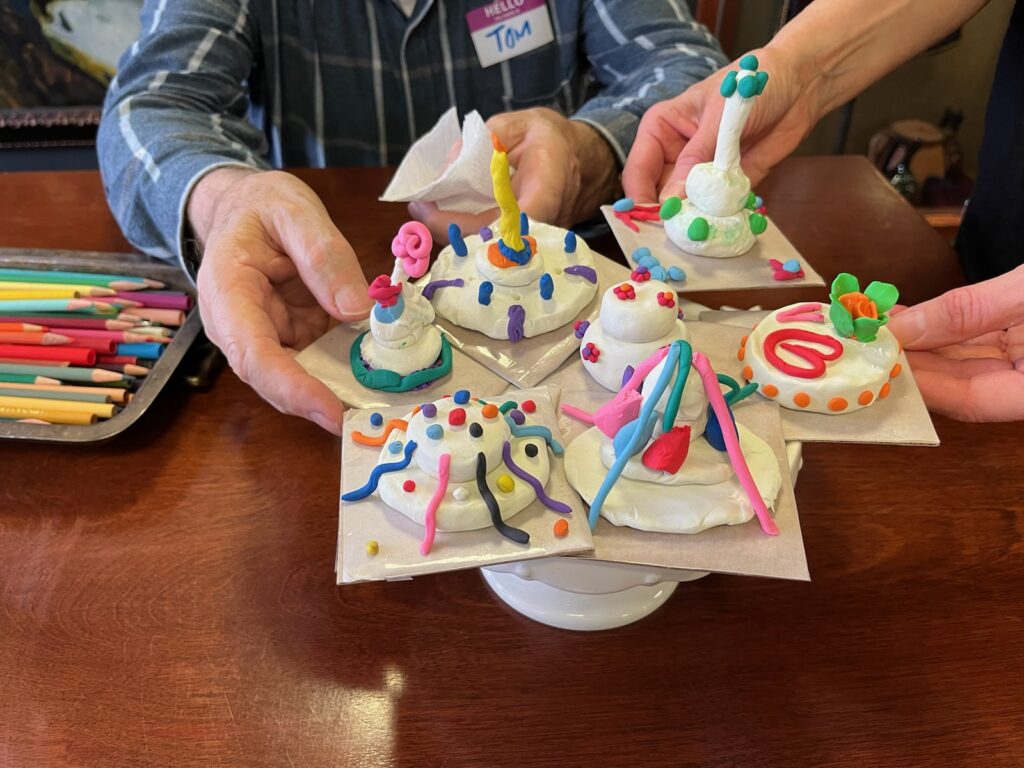

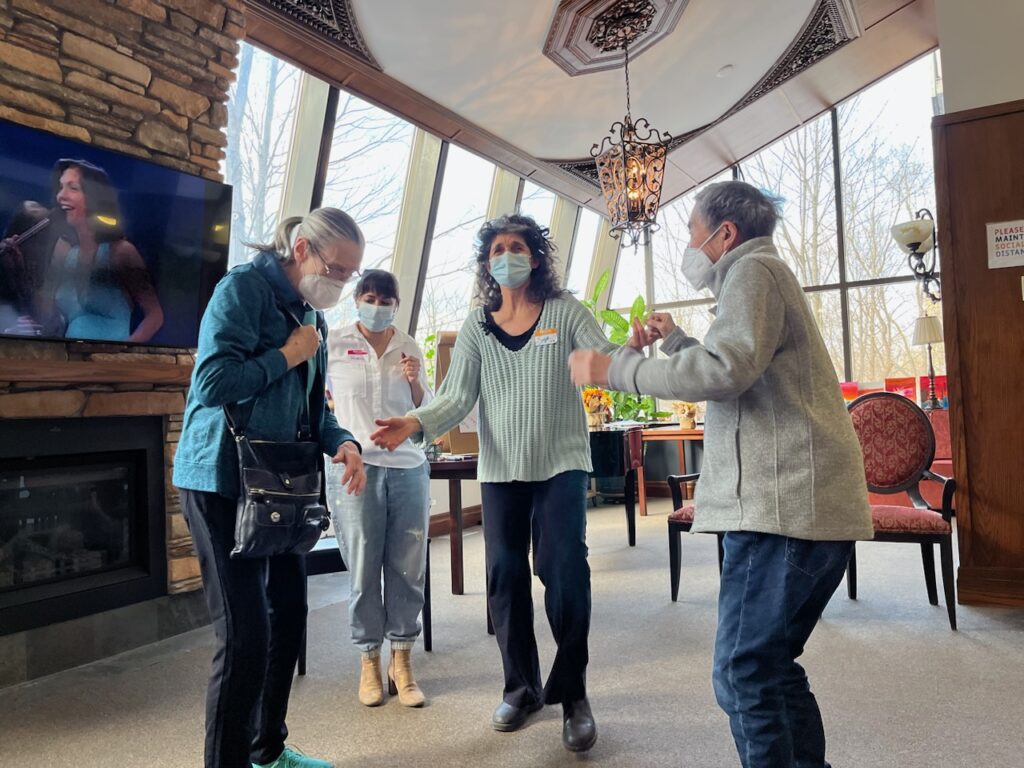

When Pat walks in every Thursday, she is welcomed with open arms and is encouraged to draw, colour or read while other participants trickle in. With Bob Marley playing in the background, one of the participants rises and begins dancing, and the occasional dance party begins. As the day progresses, participants paint, make clay sculptures and eat snacks. If they get tired, they simply close their eyes, and listen to the music and chatter around them or doze off.

Pat said her favourite part of Bitove is the snacks they get, while other participants say they love being social again and that creating art makes them feel “alive.” Charlotte said Pat’s care partner sometimes has trouble getting her to leave because she enjoys herself so much.

The program uses a unique approach to caring by using the arts, not as therapy, but as a means of connection and engagement, said Engell. Expression with the arts provides a level playing field to participants. Many of them are at different stages of memory loss. Some can communicate more than others, or differently, but they’re still communicating, she said.

“What we try to do is find ways to use the arts and community building to tap into that other part that’s still around and it’s incredible to see how once you do start shifting the focus onto capacity and reciprocity, and just being in the moment together instead of trying to reach some goal around fixing, it’s incredible how much those parts start to shine through,” Engell said.

With an aging population and the pandemic shining a light on the gaps in long-term care facilities, a greater need exists for these kinds of programs, she said.

By the year 2046, the number of Ontarians aged 85 and older could triple to 2.5 million, according to Statistics Canada. This is one of the fastest-growing age groups, with a 12 per cent increase from 2016 to now. These numbers put increased pressure on all levels of government for more support in long-term care facilities but also raise concerns about people aging in their own homes and the supports they need.

Pat lives at home with Charlotte and attends one other day program twice a week. Charlotte says her mother is less responsive at the other program because it is a larger facility with less one-on-one interaction. Bingo is played frequently there, but Pat hates bingo. At Bitove, Pat can connect with the activities and is free to express herself however she feels most comfortable that day, Charlotte said.

“It’s almost like she’s going to someone’s home instead of a big facility with a huge bright lit room. It’s got a fireplace, they have trees, they know her face, so it’s like she’s going to someone’s home every Thursday, and she’s got this extended family there,” she said.

Focusing on caring “with” someone rather than for them puts agency back on individuals who are experiencing memory loss and gives them a sense of autonomy that is often taken away in other care facilities, Engell said.

This method of caring is the long-term goal, but there is still a long way to go. Long-term care facilities are underfunded and understaffed, and government politics don’t always advocate for older adults, she said.

“Older adults definiatly get left in the dust a lot more often,” she said. “But, I think we’re onto something here.”

Engell and her team compare their program to a flock of birds that move together and are responsive to each other, creating flowy shapes, like a murmuration of starlings.

“We’re all moving together in this sort of nebulous way where you don’t always know how it’s going to take shape that day but it just does and we flow together and we don’t bump into each other,” she said. “That’s how it feels at the Bitove Method.”