By Lauren Battagello

Lorraine Lam says she’ll never forget the first time she was unsuccessful in resuscitating someone who overdosed.

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, she and another outreach worker got called to respond to an overdose at a tent on-site at a shelter she worked at in the GTA.

Performing CPR and other lifesaving measures was not new to Lam—one of her first jobs was as a lifeguard.

Lam said when the EMS arrived on the scene, it seemed to take them a long time to put on their protective equipment in keeping with pandemic safety guidelines.

She didn’t have time to stop and ask what was going on, though, because she was too busy doing chest compressions.

“I could hear one of the firefighters say, ‘Oh, you should really have a face shield on.’ And I was like, ‘No shit, that was not my priority in the moment. We have somebody dying.’”

A first responder came up behind Lam, who was still performing CPR, and placed a face shield over her head, encouraging her to keep going, that she was “doing great.”

“I was like, ‘What? Aren’t you the one who is supposed to take over at this point because you’re the firefighter?’ The whole thing was very confusing, and it all happened so fast.”

As COVID-19 numbers began to rise across Canada in 2020, so did the number of overdose deaths, especially in homeless shelters. Shelter residents having to comply with social distancing rules had no choice but to break what has been dubbed the “golden rule” of drug use: never use alone. With shelters also dealing with understaffing and month-over-month increases in the number of people seeking shelter, Toronto has reached a critical point in the crisis.

“As time has gone on, [overdoses] have become such a regular part of our day to day that we don’t even do [critical incident meetings] anymore because it’s just the new normal,” said Lam, who now works as a community outreach coordinator for Sanctuary Toronto, a non-profit that works with the unhoused.

Last year in Toronto, the number of opioid overdoses in shelter settings crept into quadruple digits for the first time: 1,563 overdoses, up 83 per cent from the year before, according to city data outlining overdoses in homelessness service settings. 67 of those 1,563 resulted in death, up from 46 deaths in 2020. The opioid crisis has hit Toronto’s unhoused community exceptionally hard: 2,090 for every 10,000 people experiencing homelessness in the city would have experienced an overdose last year; for the general population, the number is only 10 per 10,000.

Lam said that understaffing and poorly trained staff helps explain why the numbers are so massive.

“If you have staff who don’t know, who aren’t trained to respond to overdoses, or not enough staff to support overdoses, then literally, people are dying. These are preventable deaths,” Lam said.

Lam has also been cited as having suggested going as far as hiring the shelter residents themselves as harm reduction workers, because of the knowledge of the system they could bring to the table.

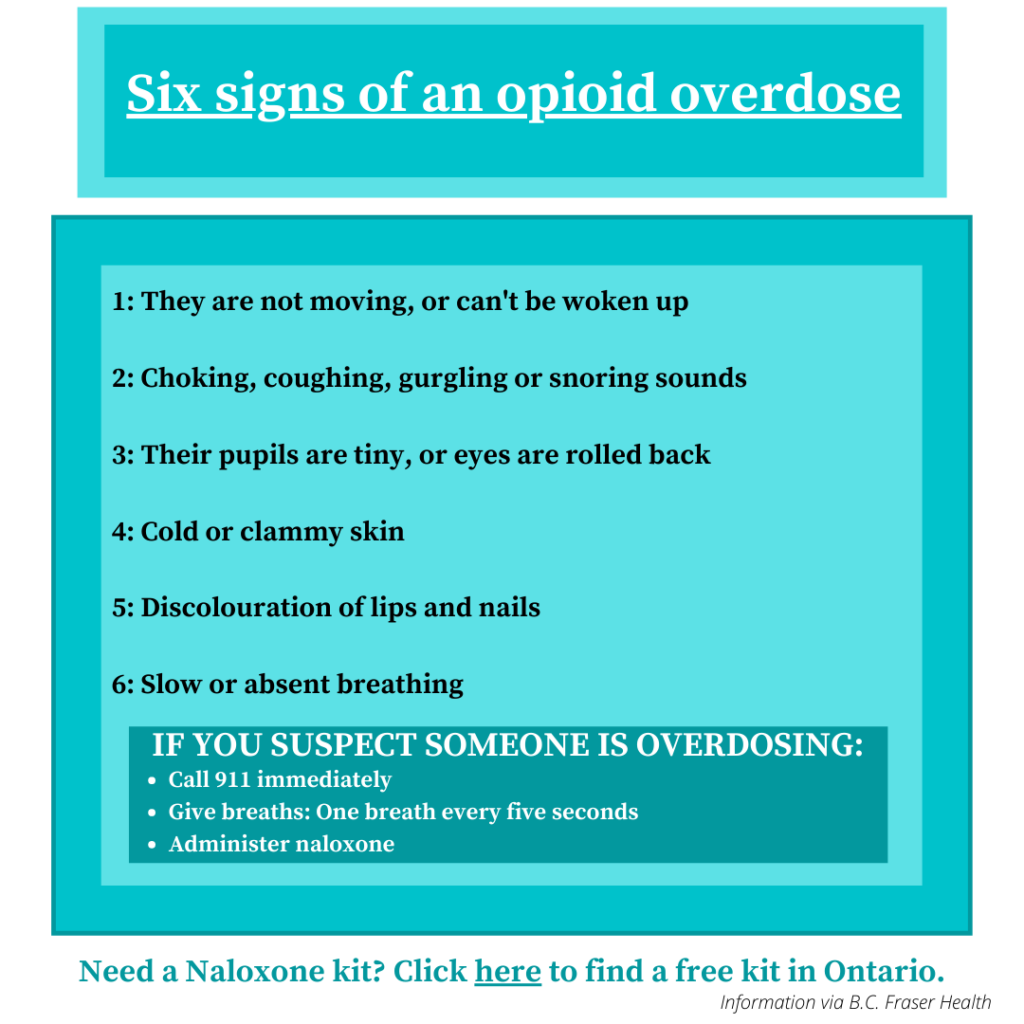

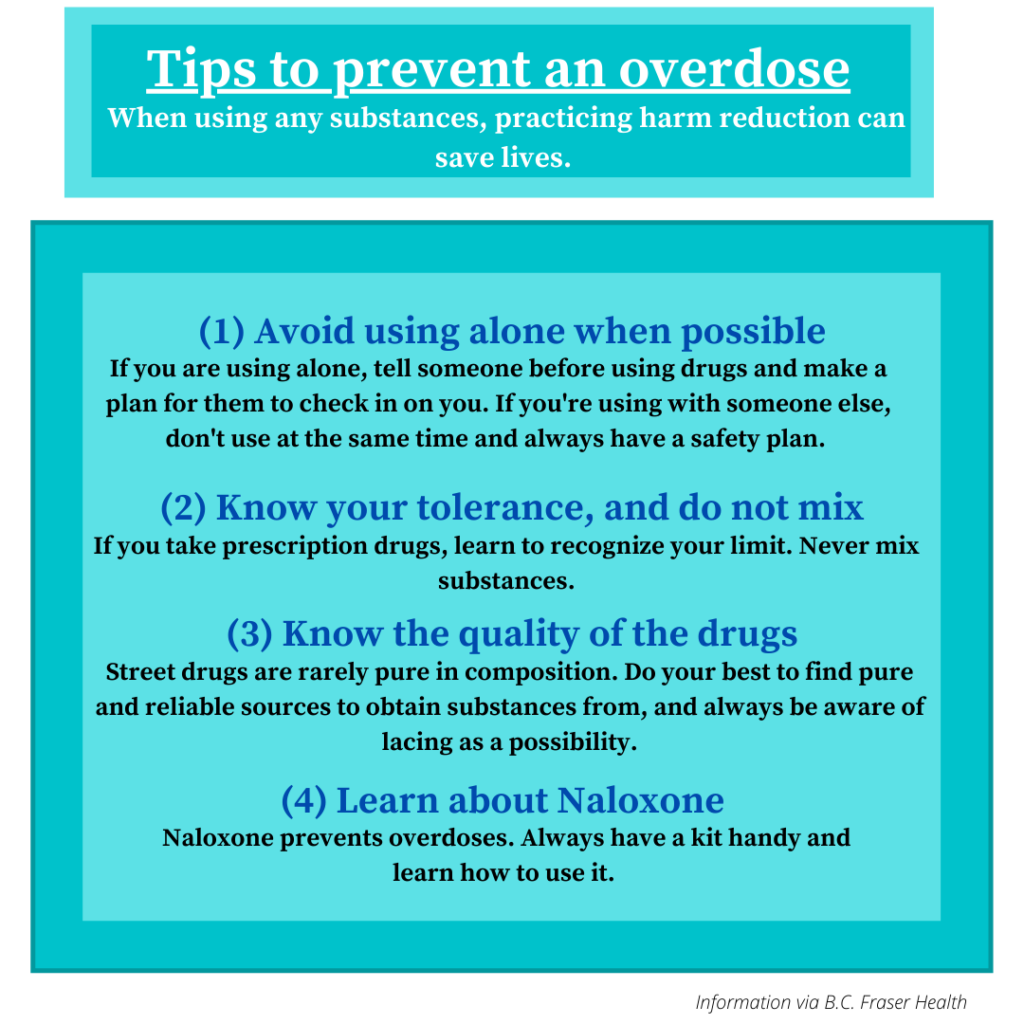

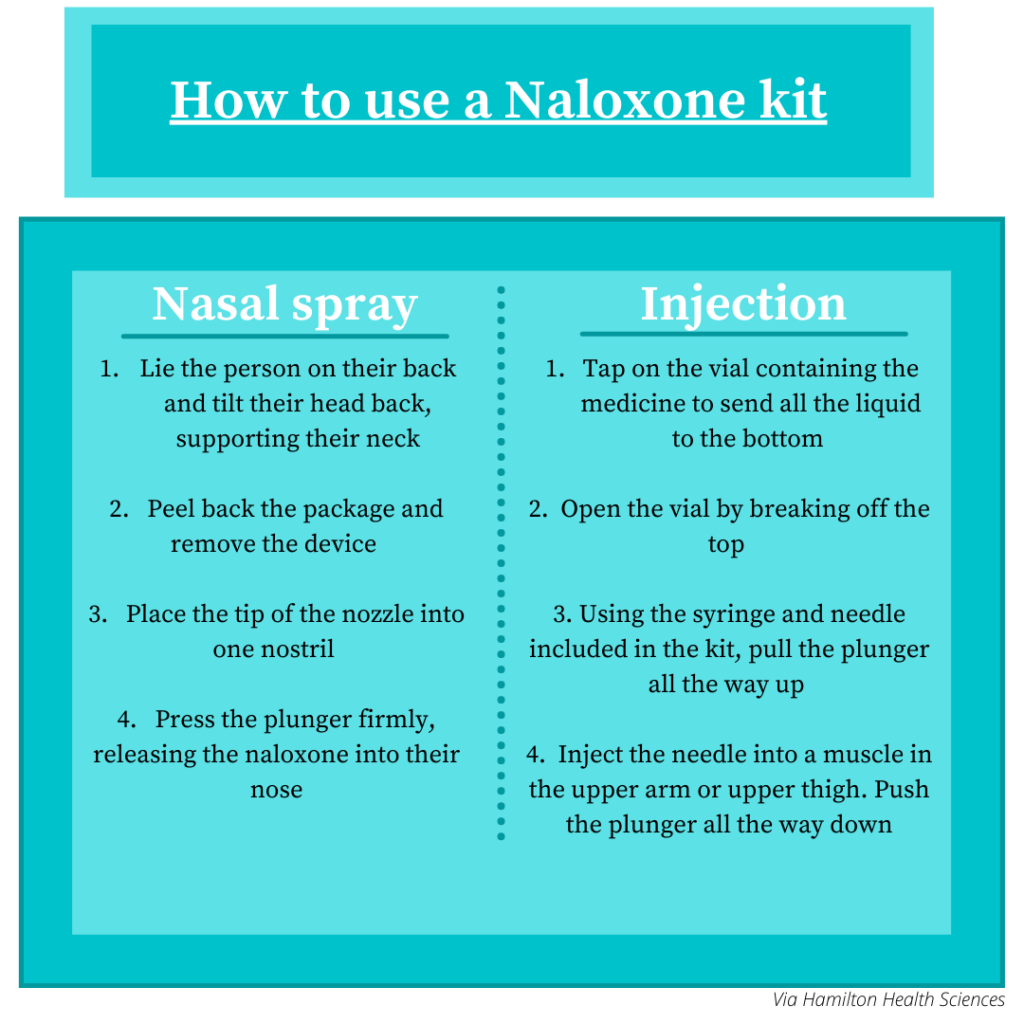

In response to the rapidly increasing number of overdoses in shelters, the City of Toronto introduced an initiative called the Integrated Prevention and Harm Reduction Initiative (iPHARE) in December 2020. iPHARE provides harm-reduction support in shelters it partners with, such as a peer-witnessing program for safe substance consumption and training on naloxone, a medication used to reverse the effects of opioids.

In a statement, the City didn’t address staffing issues, but emphasized the plans for more community outreach to ensure people were getting access to harm-reduction services.

It also acknowledged that one of problems is the volume of unsafe supply and tainted substances making its way into shelters.

“Drug-checking services in Toronto continue to detect unexpected, highly potent drugs in samples checked in recent months, including ‘ultra-potent’ opioids and benzodiazepine-related drugs. This shows that the unregulated drug supply in Toronto remains unpredictable and toxic,” the city said.

It also emphasized the plans for more community outreach to ensure people were getting access to harm-reduction services.

Shelter workers are feeling the strains of unsafe supply fighting back against their outreach efforts.

“There is no regulation or control over the types of substances that folks are using,” said Melanie Smith, the supervisor for community engagement at Dixon Hall, an organization that works with vulnerable populations in Toronto. “It speaks to a larger systemic issue that we have that speaks to drug regulation.”

“It’s really about working together, and working together with the city and with other levels of government in order to effectively support people who use drugs.”

According to Lam, the problem stretches beyond matters of safe supply, to why people end up in the shelter system in the first place.

“To me the conversation around safe supply is closely linked to the conversation around trauma and poverty,” she said. “We need to be prescribing from a trauma-informed lens so that there isn’t a stigma attached to people using it. You can’t pursue any form of stability in your life if you die from an overdose.

“How many people have to die before they take this seriously?”