By Mathieu Sheridan

The darkness has become one with yourself. Lying down is the only time the pressure isn’t coursing through your skull. The constant mix of nausea and dizziness has caused many long days that never seem to end – the world is forever spinning like a top. The days without symptoms seem like a distant memory. Simply functioning and doing everyday tasks seems daunting. The will to push forward keeps diminishing, but the hope that one day it will subside is what keeps one pushing forward.

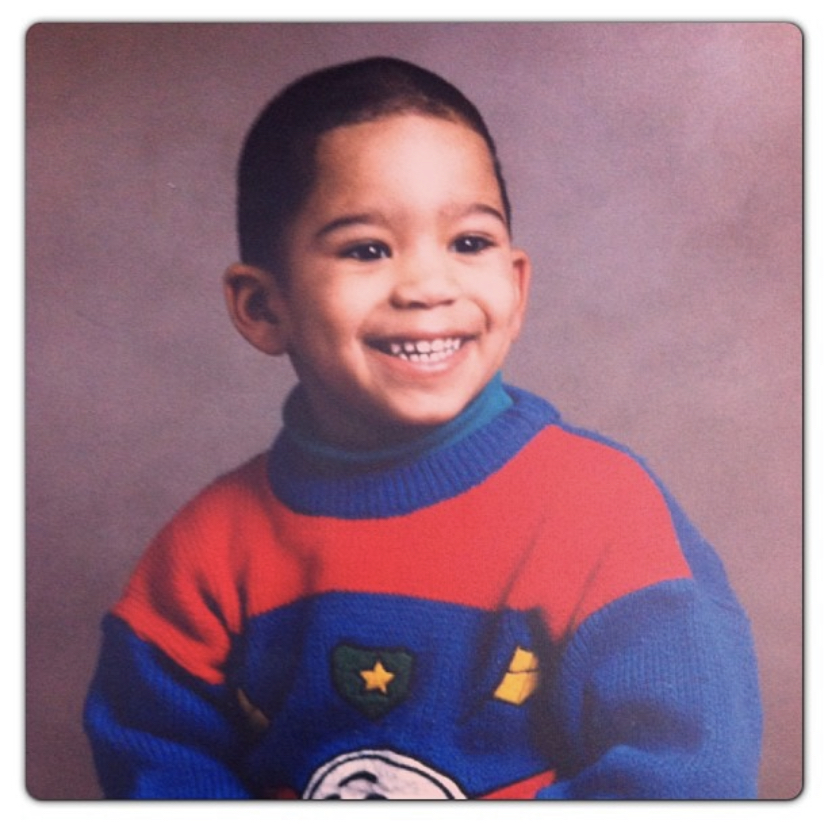

This sort of scene was familiar to Arron Alphonso. Having suffered 14 concussions, he was forced to give up hockey to keep his health. According to Cary Keller, a specialist in sports medicine, the incidence of concussions during games in the NHL is 6.1/1000 athletic exposures, a close second to football. Arron’s situation – with more than twice the number of that astounding average -seemed bleak, but instead of letting his injuries take ahold of him, he recovered and returned to the game as a coach to speak about his experiences.

Like many young kids, Arron had aspirations to play professionally, though, with the severity of his injuries, he knew that wasn’t going to be possible. His post-concussion syndrome (PCS) launched him into a downward spiral of emotions and symptoms. From severe light sensitivity to massive headaches from small movements, his quality of life suffered.

Speaking about the ordeal, his shoulders sink and his eyebrows knot: “If I ever exercised or pushed my eyes to follow things, I definitely invoked symptoms. Anytime I got my heart rate up, I would get symptoms.” he said.

Arron suffered from depression, and at times found himself unable to do anything overtly physical.

“If I did anything outside of that area, I would be feeling concussed. It was definitely one of the toughest times of my life.”

To those close to him, they remarked on the change as well. It was a worrying time for his friends and family.

“When I first met Arron, there was like a dark cloud around him,” said his friend, Pamela Wilson. “He said he suffered some really bad headaches, didn’t sleep well and was very depressed.”

“That was a really difficult time for me to see him go through that,” said Shandor Alphonso, his brother. “He was in a really bad state and I was worried about him.”

Playing at such a high level of hockey – as a right winger -Arron had to continue pushing through his concussion issues from throwing up during intermissions to feeling the daily pressure to prove himself. He retired at the age of 22, no longer able to handle the pressure of having the compounding symptoms. He wanted to play but needed to heal above all else.

“As athletes, you’re like a piece of meat. When you’re not a good piece of meat, you’re looked at a lot differently than when you were a good asset,” he remarked.

Arron also mentioned how it was tough to experience a process like that. He spoke about how he always had a deep love for the game whose harsh reality became more obvious once he tried to play while injured.

“You started to see the different colours of the game,” he remarked. “It’s never easy to be treated like that, but at the same time, you understand it’s a business at the higher levels.”

While he continued to deal with PCS long after he retired, Arron was able to get better through physiotherapy and alternative medicine. A long and arduous journey, he returned to coach to help guide others. In a way his recovery from the staggering number of concussions and the long-lasting symptoms is a testament to his perseverance and athletic mindset.

As a coach with the North York Rangers, Arron made sure he was open about his own experience and used parts of his journey as a cautionary tale to show others the seriousness of concussions. Since hitting is a major part of the game at a high level, he wanted to stress the importance to his players that proper recovery from head injuries is key.

“I was coaching junior hockey and I was only three years older than some of the guys,” he said. “I was fresh out of the game showing them in practice I could still be playing for another 10 years, but this is the product of that experience of pushing against the flow of how things are going and trying to force yourself back into the game.”

Like Arron, many players still deal with concussion troubles. Although he saw a lot of improvement when he was a coach, PCS is still prevalent in the sport.

“While fighting has been reduced in sport, it still happens,” said Dr. Ryan Scott, a concussion specialist. “Until they say fighting is not a part of the game, in my mind, they are still sanctioning it and that is why [concussions] are still prevalent. We definitely need more advocacy. We’ve just got to keep pushing it.”

While he has had so much taken from him, in helping others deal with their own concussion issues, Arron was able to find a different purpose that kept him involved with the game he loved so dearly. Although he wishes the journey unfolded in a different way, returning to hockey allowed him to find some comfort.

With 10 years having passed since his retirement, Arron has been able to reflect on the different experiences being at the rink provided him. He was quick to point out that hockey has also given him some of his fondest memories.

Having grown up near Toronto, Arron was situated in the hockey mecca of the world alongside many passionate young hockey players.

“It was awesome,” he said about playing hockey as a kid and calling Orangeville, Ont., home. “I lived about an hour from Toronto but from 10-years-old, I was always playing in the city. You meet a lot of different people from all kinds of places and I think that was one of the fondest memories that I’ve had.”

The game also afforded Arron the opportunity of suiting up with his brother Shandor. After his Ontario Hockey League career finished, Arron got to share the ice with him while playing for Lakehead University.

“We grew up so differently,” said Shandor. “I moved away to play hockey. Once we got to play together, we were both men at the time. It was kind of nice to form a great friendship.”

Now, 5 years later, Arron has been out of coaching for a while but he’s still found a way to his work meaningful. Today, he’s now working as a support worker in Ottawa. While not directly involved in sport, this line of work is no different than what he’s done in the past: helping others.

A smile beams across his face when asked if he would like to return to hockey in the future.

“I’d love to return to the game at some point,” he said. “If the opportunity presents itself, I would certainly take it.”