By Nishat Chowdhury

About 15 years ago, a very pregnant Zaibunnisa ‘Zaiba’ Butt would haul a full-sized suitcase jammed with traditional Pakistani clothes from door to door. Before leaving home, she would call customers to get a list of their preferences in size, colours, patterns and materials, then ask her husband or brothers to drop her off nearby so she could make the deliveries.This arrangement made her reliant on the men in her life, but not as much as they would have liked. Her seven brothers once tried to bribe her — offering a weekly $20 allowance per brother — not to work, so she would fit in better with the women in her community social circle.

“I like to make my own money, have my own job,” she says today, adding that she managed to keep the intended bribes despite continuing to work and eventually opening her own shop in the basement of her home in the Clairlea-Birchmount neighbourhood of Scarborough.

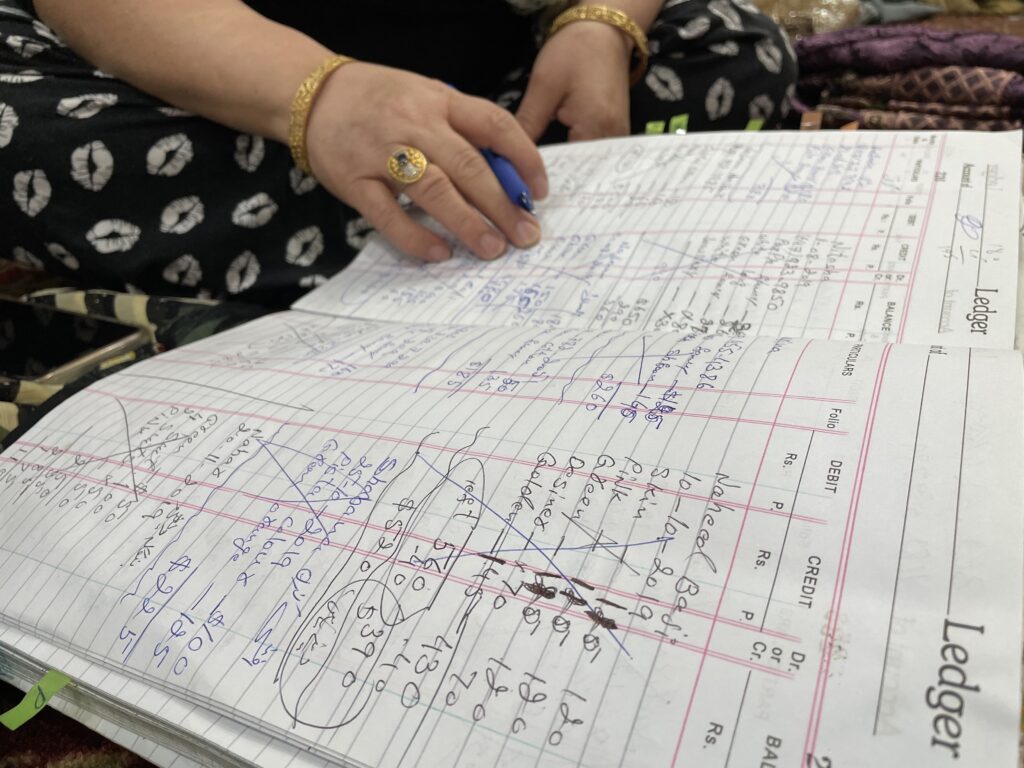

Since Zaiba operates out of her basement, she doesn’t have to pay additional overhead costs like electricity and rent, or even staff salaries. That allows her to charge lower prices for high-quality designer suits than the stores on the Gerrard India Bazaar strip and the huge South Asian clothing stores in the suburbs of the Greater Toronto Area, which charge almost twice as much.

“Because I’m selling, my mortgage, bills, everything is running because of my business.”

Zaiba Butt

When she immigrated to Canada in 1999, she took a series of jobs, from Coffee Time to a short stint at a factory, and then to Pizza Pizza– never considering it an option not to work.

“When I came to Canada, I’m thinking I can do something here, because this culture is different. Whatever a man does, a lady can too,” she said recently during an interview at her shop.

Starting her own business was a slow process and grew from those early days selling door to door. She recalls that when her brothers tried to convince her to quit, they were being fed doubts by friends and community members who suggested she wouldn’t succeed.

When she refused to quit, they questioned her respect towards them.

“I said respect is one side, my business is another side. In business, I have no brother, no sister, no mother, no dad. My business is my own business,” she recalled telling her brothers.

These days, Zaiba’s work is a lot less back breaking. A homeowner now, her basement has been converted into Zaiba Boutique, where she sells Pakistani dresses for weddings and parties, and casual wear for women and kids.

Five years ago, her husband was able to quit his job at a gas station to be a stay-at-home dad to their three kids and to give her time to invest in her boutique.

“Because I’m selling, my mortgage, bills, everything is running because of my business,” she says, gesturing to the upstairs living quarters and back down to her inventory .

During peak business times, such as wedding season in the summertime and around both Eids, Zaiba can be found downstairs helping customers from the morning into the late night.

The basement floor is covered with a soft, red-patterned carpet and the walls contain built-in shelves with racks of suits. Embroidered tunic style kameez and dyed kamdani suits with culottes-style shalwar pants are on display, alongside regal-looking dresses. Mannequins are adorned in fancier, bejeweled suits and one area has been sectioned off with red curtains to serve as a makeshift changing area.

While browsing, the faint sounds of children speaking and footsteps walking upstairs can be heard from up the staircase that separates Zaiba’s job from her family life.

The Pakistani suits on display have straight silhouettes and longer sleeves than Indian suits, which are popular for their A-line silhouettes and short sleeves. These fashions appeal to Muslim customers looking for modest styles, Zaiba explains, which helps her compete with local alternatives for fashion such as The Gerrard India Bazaar.

Known as “Little India”, the Bazaar has been a draw since the 1980s, according to research published in 2010 by Ryerson University. At one time, the enclave in Toronto’s Leslieville neighbourhood contained about 100 South Asian shops and restaurants, and was visited by more than 100,000 tourists in 1984.

In the last two decades, however, Little India has lost out to the suburbs of Brampton, Mississauga, Scarborough, and Markham as many South Asian families have moved there and new businesses sprung up there to cater to them. A confusing mix of parking restrictions has also made the area less inviting to shoppers, according to Tasneem Bandukwala, manager of the Gerrard India Bazaar Business Improvement Area.

“If a customer gets a ticket, they might swear and say I’m not going to Gerrard again,” she said.

Zohora ‘Kanta’ Mahamuda, who used to shop often on Gerrard Street, remembers the first time she met Zaiba. It was on a hot summer day about 15 years ago, when she stumbled across Zaiba’s booth at a Bangla mela (fair). In those days, Zaiba would supplement her door-to-door visits to customers by renting out a booth for $500 and selling her wares at such markets. She would also keep business cards in her purse at all times, handing them out at retailers such as Zellers and Walmart, and even at doctor’s offices she visited. Kanta remembers being intrigued by the only non-Bangladeshi vendor at the fair in Dentonia Park.

Since that day, Kanta rarely shops for South Asian clothes outside of Zaiba Boutique. She made an exception briefly last year when Zaiba closed at the height of the pandemic. Kanta had to resort to online shopping from boutiques in Mississauga and Markham, where she says she felt the prices were too high.

She has other reasons for preferring the basement boutique, too.

“Zaiba can give me the solution, don’t go for this, or go for that, that kind of stuff so I always look for that. Those places don’t do that,” Kanta said while shopping on a recent February day. She scooped up about a dozen items in an hour and a half, spending $900.

Another loyal customer, Thamina ‘Farhana’ Chowdhury, helped spread the word about Zaiba’s business in the early days — not just by word of mouth, but also by bringing customers to Zaiba’s door.

Dressed in a pink floral print nightgown, her breath minty fresh from brushing her teeth moments before, Zaiba was fluffing her pillows before climbing into bed. It was about 11 p.m. and suddenly her iPhone started ringing.‘Farhana’ flashed across the screen.“Hello, Asalamualikum,” she answered slowly in a customary Arabic greeting, confused as to why her customer Farhana was calling her so late that spring night in 2016.

“Zaiba, open the door. I’m outside your door with a couple of customers and they need a couple of suits. Hurry up,” Farhana said, half yelling.

With the phone to her ear, Zaiba glanced at her husband with hesitation, silently searching for advice, but before he could answer, she said:

“Okay no problem, I’m coming.” Hanging up quickly and grabbing a black scarf to loosely wrap around her head, she rushed down the wooden stairs of her home to answer the basement door for the customers waiting outside.

Farhana says Zaiba is “outgoing and bubbly” and explains that she was keen to help the shop succeed. “Everyone likes her because of her kindness and the way she speaks to people,” she said. “As a fellow Muslim, I wanted to help her increase her business and help her out.”

Zaiba recalls Farhana’s late-night visit as a time when she had a hard time setting boundaries between her business and her family life. Desperate to make money, she would let customers come even at inconvenient times for her and her family. During Ramadan nights, some customers would even show up past 1 a.m. to make purchases before Eid al-Fitr, which is celebrated after 30 days of fasting.

“I cared too much. Anytime a customer called me to tell me they were coming, I would say okay no problem, okay no problem,” Zaiba said.

While she is still fiercely committed to the business and her central place in it, she is now on more solid footing and her personal boundaries and family priorities have grown stronger.

“Now I tell people, you come at 7 or 8 o’clock, if you can’t, come (back) another time.”