By Callum Denault

“For a lot of athletes, without their sport, there aren’t as many options that are as accessible for them to be able participate”

The court is ablaze with rapidly turning wheels and churning passion. Sometimes athletes ram their wheelchairs into opposing players with the same ferocity of clashing bulls, other times they deftly shift and turn on a dime in an attempt to beat their rival to the goal.

The crowd’s cheers echo through the building in waves, lowering in anticipation of each play’s outcome, then exploding into applause for every goal, save and turnover. It’s the 2012 Paralympic Wheelchair Rugby semifinals, and Canada has just beat the United States by a single point, earned in the game’s last half second. It is also when Patrice Dagenais achieved his childhood dream of being an elite athlete.

Almost ten years later, at the age of 37, he is still training and competing, having reached his fastest time while preparing for the 2021 Paralympic Games in Tokyo. However, the impact of para sport on Dagenais runs even deeper than his adrenaline fuelled moments in the spotlight. The world class athlete says he owes wheelchair rugby his independence.

Dagenais was an avid hockey player before he acquired a spinal cord injury during a construction job accident in 2003. Para athletes often visit quadriplegics and people who have experienced injuries, both to provide social support and also to recruit new players. Initially Dagenais has little interest in wheelchair rugby–saying that in his case, he was not yet ready to accept not being able to walk or play hockey again–but he attended a practice anyway out of respect for the athlete who visited Dagenais in rehab and invited him to play on The Ottawa Stingers. When he arrived, Dagenais met other people with injuries who were not only playing para sports, but had families, could drive and had their own houses.

“I met other athletes who went through similar challenges and had a very similar disability,” said Dagenais, “I saw they were able to be independent and could do things on their own.” He said it took him four to five years to be fully independent, owed to strength training in wheelchair rugby and tricks he learned from fellow athletes.

When the COVID-19 lockdown hit, it was even more smothering for people with disabilities than able-bodied members of the public as existing barriers were exacerbated by the pandemic, said ON Para Network high performance manager Josée Matte.

“For a lot of athletes, without their sport, there aren’t as many options that are as accessible for them to be able to participate,” said Matte, “Without that organized, structured club system, they might not have the equipment they need to even go for a bike ride with their family. In the winter especially, sidewalks are icy, there’s a bunch of snow or maybe roads aren’t being plowed, so they can’t go for a walk or wheel around the neighbourhood because it’s just that much more inaccessible.”

However, Matte also said the switch to online work and education during COVID-19 allowed people with disabilities accommodations they otherwise had to fight for.

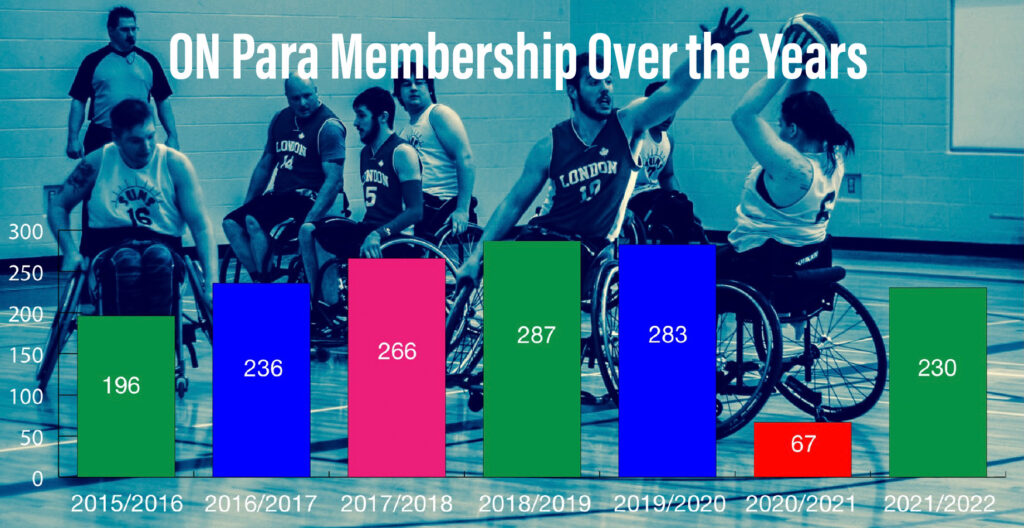

During the 2020/2021 season, the ON Para Network lost 70 per cent of its pre-COVID athlete participation due to a lack of available programs, said Matte. This year, that deficit shrunk to only a 40 per cent loss, which Matte attributes to programs having returned. Sammy Feilchenfeld—training manager from Volunteer Toronto—said while more people are interested in volunteering, less are going through with it. Volunteer Toronto’s website used to have 600-800 postings at the end of a given day, and the number of postings is now around half that.

“There’s less opportunities available, and some people are tired of virtual volunteering or some people don’t feel safe.” Said Feilchenfeld.

“We know that thousands of charities and non-profits have shuddered because of the pandemic over the last couple of years,” he said, while discussing a general decrease in the already stringent amount of funds charities receive, “we know that number will likely grow.”

While socially distanced communication has made work and school more accessible, Matte noted virtual workout programs were not always feasible for people depending on their physical capabilities, home environment and access to equipment. Furthermore, pandemic-induced social isolation dealt a major blow to mental health and wellbeing.

“Someone who really helped me was the coach of my home team [The Burlington Vipers], whose name is Chris Chandler,” said Vanessa Giancaterini, a high performance wheelchair basketball athlete who also trains on Team Ontario in addition to her home team.

“During the pandemic especially, he was there for me helping me train, and there for me emotionally. Just being very understanding of the situation.”

Looking back on the COVID-19 lockdown, Dagenais said, “One of the things that hurt the most was recruitment and the fact we may have missed some people.”

Because para athletes were not allowed to visit rehab centres during COVID-19 — such as how an athlete visited Dagenais during his rehabilitation in 2003 — there may have been potential athletes ON Para could not reach. Conducting volunteer recruitment activities and public events with other para sport organizations is the other major way the ON Para Network recruits new members, but this was not possible either.

The next step for the Ottawa Stingers is finding a new facility, which Dagenais has so far had no luck in succeeding.

“The gym we used to go to was a school on Thursday evenings,” said Dagenais, “and it’s still not open for us to practice.”

Their current weekly practice time at 4pm on Tuesdays is less than ideal.

“[…] there’s people who can’t make it, because of work or school.” He said.

Matte said most ON Para club practices and the majority of tournaments were held in school facilities – such as high school gyms – which is an issue now that school boards are unable to issue permits. There is more demand than available gym time.

Feilchenfeld said finding facilities is a large barrier for many sport charities in Ontario. While several clubs operate under the guidance of a larger organization—such as how The Ottawa Stingers are part of the ON Para Network—Volunteer Toronto has noticed countless startups which began from something as simple as a small group of condo or apartment building residents organizing games for their neighbours’ kids at the local basketball court.

In any case, clubs big and small, united and isolated are struggling to find spaces to play in as they expand. Feilchenfeld gave the hypothetical example of someone waking up at 6am on a Saturday in January to book a practice in August.

“With those people who are active, they’re behind a year — at least — in their skills,” said Heather Harflett, who volunteers as a high performance director on Giancaterini’s team.

The Vipers have three separate streams—a recreational stream, a competitive stream, and a development stream for athletes aged 17 or younger—and has athletes both with and without physical disabilities playing together. With less people attending, athletes from different divisions are now practicing with each other more.

“There’s going to be—hopefully—a lot more mentoring regardless of how we set up the streams,” said Harflett, adding the three streams give a space to everyone regardless of their ability level, but mentorship allows greater skill transfer between teammates. When discussing one development athlete who improved enough to join the competitive stream, Harflett said she helped that individual grow.

Special Olympics Ontario (SOO) — an organization focusing on athletes with intellectual disabilities just as para sports focus on those with physical disabilities — has experienced similar turbulence to the ON Para Network.

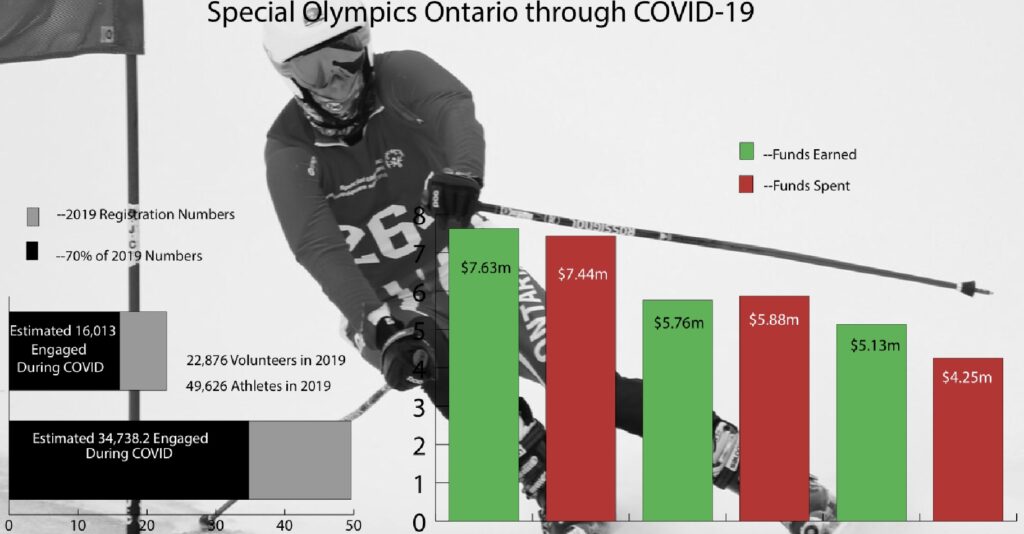

Kirsten Bobbie—who used to be a programs manager for SOO before she left to work at Special Olympics Canada—cited a report that said SOO had 49,626 athletes and 22,876 volunteers registered in 2019, both of which were new records. She estimates that 60 to 70 per cent of these athletes and volunteers stayed engaged through virtual programming during lockdown.

“[W]e asked [our volunteers] how to rank what type of support they felt they’d need coming out of COVID,” said Bobbie. “Overwhelmingly, I think it was 54 per cent of people stated they would need help recruiting volunteers. That tells us even our volunteers know they’ll be short volunteers as we come back in person.”

In 2019, Special Olympics Ontario made $7.63 million and spent $7.44 million, with both figures dropping by $2 million in 2020, resulting in SOO spending $100,000 more than it earned that year. In 2021, SOO earned $5.13 million and spent $4.25 million.

Both Bobbie and Matte said their respective organizations plan on using a hybrid model, offering in-person and virtual programs to be more accessible while reaping the benefits of both.

Bobbie said as programs are rebuilt from their grassroots, Special Olympics Ontario and organizations like it can utilize newfound partnerships and online tools that likely never would have been thought of if not for COVID-19.

“Communication burnout is one thing,” Harflett said., “Now it’s all zoom or emails and that’s really tiring. But at the end of the day I remind myself we’re running this program that helps a lot of people, and for me that sense of reward that I’m helping someone motivates me.”

(Note on language: this article uses person-first language, i.e. “person/people with a disability”. This is in contrast to identity-first language, i.e. “disabled person/people”. All sources from the ON Para Network–including those who identified as having disabilities–said they preferred person-first language, and Special Olympics Ontario also uses person-first language in its official media.)