By Aneesa Bhanji

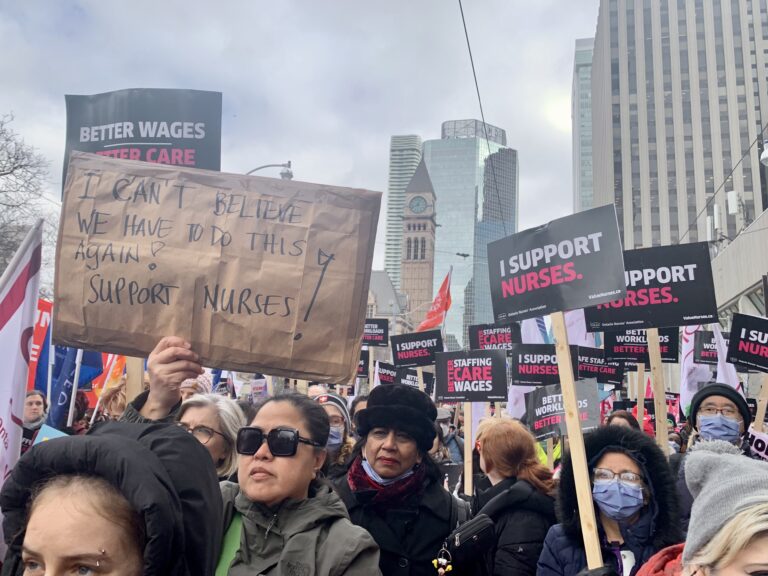

On a sunny winter afternoon in Toronto, hundreds of people crowded the intersection of Bay and Queen streets. Groups wearing neon pink toques and waving vibrant triangular flags hoist their picket signs up high. Phones were popped out of pockets and journalists adjusted their cameras to get the best shot. The beat of a drum synchronized with the words chanted, “Pay nurses what they’re worth! Pay nurses what they’re worth!”

The protest, organized by the Ontario Nurses’ Association (ONA), drew health-care workers from across the province to demand better wages, more staff and improved working conditions. The nurses say they feel burnt out and their pay does not compensate for the physical and mental demands of the profession. Data from Statistics Canada in 2022 shows that almost one in four nurses intend to leave their job or change jobs in the next three years. Everyone from veteran nurses to students just entering the profession, fear that unless the system changes, conditions will only get worse.

“It’s demoralizing when you go into work and you [say] ‘I can do this’ and then you see what you’ve got. You [think] oh my goodness, I can’t do this, but I have to,” said protester Elizabeth Elliott, a registered nurse who had just finished her 12-hour night shift at Brantford General Hospital. Elliott, a health-care worker for more than 20 years, describes this shift as a nightmare.

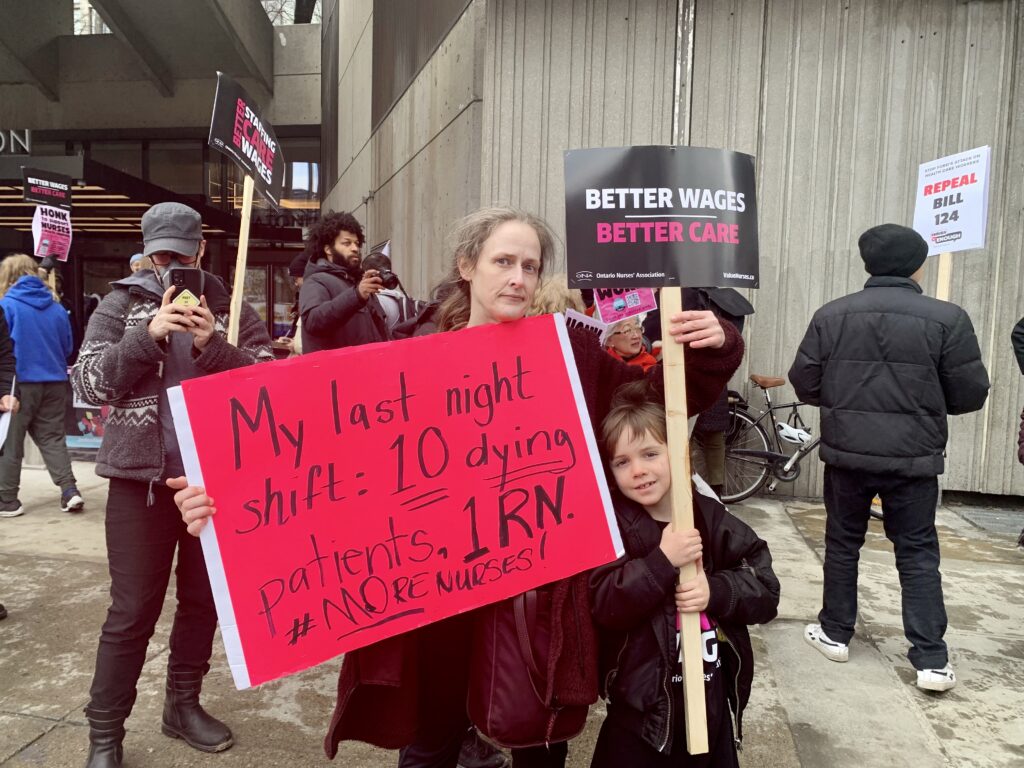

She had gone into work at 7 p.m. with one question on her mind: Are we going to be staffed today? She quickly learned that the answer to this question was no. She says she was assigned to 20 patients in the hospital’s palliative care unit. She called her nursing leader, who sent another staff member to her floor. Elliott would still need to look after 10 patients, by herself. This contrasts to the ONA’s best practice ratio of one nurse for every four patients.

As she walked down the hall, all she could think was: “My assignment has 10 people who are actively dying. How am I going to do this?” After checking in on a few patients, Elliott was consumed with scattered thoughts: “Do I need to call the family for this person? This person’s breathing has changed since I saw them last. This person needs pain meds. Oh my God, they haven’t had them in eight hours.”

The hospital, Elliott says, has a designated crying room.

“We’ve taken one of our old showers that doesn’t work and we’ve put a curtain up. People go there and [say] ‘I need to take a break’ and they go to cry in the shower.”

Elizabeth Elliott

When asked about this story, Linneah Tovstiga, a communications specialist at The Brant Community Healthcare System, wrote in an email: “We do not currently have a crying room in place at Brant Community Healthcare System.”

She also shared a statement from chief human resources officer Erin Sleeth, which read: “It has been a difficult few years in health care with many organizations, ours included. Heightened pressures and anxiety on our patients and their loved ones also can lead to tension and mistreatment of our staff in the hospital, which naturally leads to distress among our frontline teams.”

The organization says it’s doing its best to support its staff through these challenges. “This includes increasing our focus on wellness, including a brand new peer support program that offers emotional and mental supports in debriefing and recovering from incidents,” Sleeth said.

Elliott says her experience does not stand out. This is now the status quo for nurses in Ontario.

“Health care is in the same situation wherever you are…everyday, people are coming into work and they’re anxious. We have more nurses on leave right now because of mental health than ever before. The system is imploding,” she said.

Data from Statistics Canada in 2022 shows job stress or burnout is the most common reason why health-care workers not intending to retire are considering leaving or changing their jobs.

Birgit Uwaila Umaigba, a clinical nurse specialist at Lakeridge Health, who has previously worked as a travel nurse at over 25 hospitals across Ontario, says she has seen this firsthand.

“I saw so many experienced nurses leave the profession, leaving bedside nursing [to pursue] other areas like public health or administrative roles, because it was just too much,” Umaigba said.

Samah Bhamani, a fourth-year nursing student at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) says being a bedside nurse is not her ultimate goal.

“I would like to work bedside for maybe a year or two max, but my ultimate goal is to go back to school to get my master’s degree,” said Bhamani. “I don’t want to be burnt out, I don’t want to dislike the profession…it just seems like in the direction that we’re going, nurses are not going to be respected by the province and by our legislators enough for me to feel like I need to stay.”

In 2019, Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s government passed Bill 124. The law establishes that “salary increases are limited to one per cent for each 12-month period of the [three year] moderation period,” for public sector workers like health-care professionals.

In November 2019, public sector workers challenged the government in court, arguing that Bill 124 was unconstitutional. The court decided that Bill 124 is a violation of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In his decision, Justice Markus Koehnen wrote, “I declare the Act… to be void and of no effect.”

One month later, the Ford government appealed the court’s decision.

“To have the government trying to overturn [Ontario’s Superior Court of Justice’s] decision to repeal Bill 124 is a slap in the face of every nurse or anybody who would ever need a nurse in this province,” said Umaigba.

“Shouldn’t this job that requires so much of us emotionally, physically and psychologically cover what we need to keep going? What is OUR care worth?”

— Ontario Nurses’ Association (@ontarionurses) March 23, 2023

Rachael, a nurse, shares a pretty simple demand with @OntHospitalAssn and @fordnation: You need to #SupportNurses.#onpoli pic.twitter.com/5HixT2nmRw

On the day of the rally, signs that read, “repeal Bill 124” were scattered throughout the crowd of nurses. Elliott held up her handwritten sign which said, “My last night shift: 10 dying patients, one RN. #MoreNurses!” Right by her side was her young son, Atticus St. Pierre.

Elliott said she brought her son because she wanted him to see “that this is how we make change. I think it’s really important. There was nothing violent there. There was nothing inappropriate. He just saw a bunch of nurses standing up for what they believe in.”

Daria Adèle Juüdi-Hope, a director of nursing and the president of the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO) Kingston chapter, is hopeful that conditions for nurses will improve.

“We will redefine our roles within the health care system as things shift from one government to the next. We will have better wages and working conditions,” she said. “Though change is taking forever to happen, decision makers are hearing us and will do what is required to support the health of all and support our workforce,” said Juüdi-Hope.

Elliott is hopeful that more protests like this one can help lead to change.

“I don’t think it’s enough. I think that we need to not back down and we need to continue fighting. And that’s not just for nurses. That’s for everybody,” said Elliott.

“We’re not okay. We are weary, but we’re still fighting and we’re going to win.”