By Hailey Ford

Waves lap gently against the shoreline at Pickering’s Frenchman’s Bay. The March sky is bright blue and couples walk along the shore, enjoying the warmer weather. The beach is speckled with stones and caution signs. In the near distance, the grey towers of the Pickering Nuclear Generating Station disrupt the picturesque scene and the narratives surrounding the city.

For better and for worse, the plant shapes Pickering. One of the largest nuclear stations in the world, it produces about 14 per cent of all energy in Ontario – four per cent more than Niagara Falls. Earlier this year, the Ontario government announced support for the proposed refurbishment of half of the Pickering reactors. In the fierce debate on nuclear energy, Pickering and its power plant are oft-presented as either a beacon of the future or a harbinger of destruction. The potential for disaster, economic or nuclear, petrifies those who’d prefer wind or solar energy, only to be met with a shake of the head from proponents.

Activists on both sides agree that pro-nuclear sentiment has been growing, partially due to the need for climate change solutions. “The nuclear industry has done a really good job promoting [itself],” said Angela Bischoff of the Ontario Clean Air Alliance. “They call it a nuclear renaissance.”

Environmental advocates, regardless of nuclear perspective, generally agree that clean energy sources are necessary. This is a key reason why Ontario stopped using coal energy. Where they disagree is in whether or not nuclear qualifies. Unlike coal or natural gas, nuclear power does not release greenhouse gasses and produces energy at a more reliable rate than wind or solar. However, the large amount of energy required to begin producing nuclear energy leads to concerns over indirect emissions.

While Bischoff considers nuclear a “false climate solution,” pro-nuclear activists are all-in. “It’s a non-emitting technology. There are [others] but they all come with restrictions,” said Neil Alexander from the Canadian Nuclear Society. “We have to have electricity 100 per cent of the time.”

Both activist perspectives frequently stem from outside the areas directly impacted by the presence of the generating station. To those who live in Pickering, the city is more than nuclear – it’s home.

Walking distance from the nuclear plant lies the Nautical Village, a quaint mixed-use residential and commercial community coloured by soft blue and white hues. Michele Bolton, a longtime resident, owns Open Studio Art Café, an espresso bar that hosts concerts, open mic nights, and meetups for local creatives. When asked what drew her to the area, her answer had nothing to do with electricity.

“It was cute. It was charming. Yes, it was close to the nuclear power plant. But this development just had such a draw for what I envisioned,” Bolton said. “I believe so strongly that every community needs a place that is for people to come in and say hello, grab a coffee, make a friend, go for a walk.”

Bolton said that while local activists will regularly come to drop off signs to display at her café, they’re typically about the controversial proposed airport or the Greenbelt. “Never about the power plant.”

However, in a city where over 15 per cent of residents are employed in the energy sector, Bolton is still an outlier. The plant also brings people into the city, even if they don’t stay. “We get a lot of people that are contractors that come into this area, and I will get them as a customer,” said Bolton.

According to Mayor Kevin Ashe, the refurbishment will increase the already large number of nuclear-related opportunities in the city. “[It] will generate about 11,000 construction jobs per year for each year of construction, which could be six to eight to nine years,” he said.

Ontario Power Generation (OPG), which owns and operates the plant, also sponsors a number of spaces in the city. Walking due south from Bolton’s café and making two left turns will lead to one such area, the Alex Robertson Community Park.

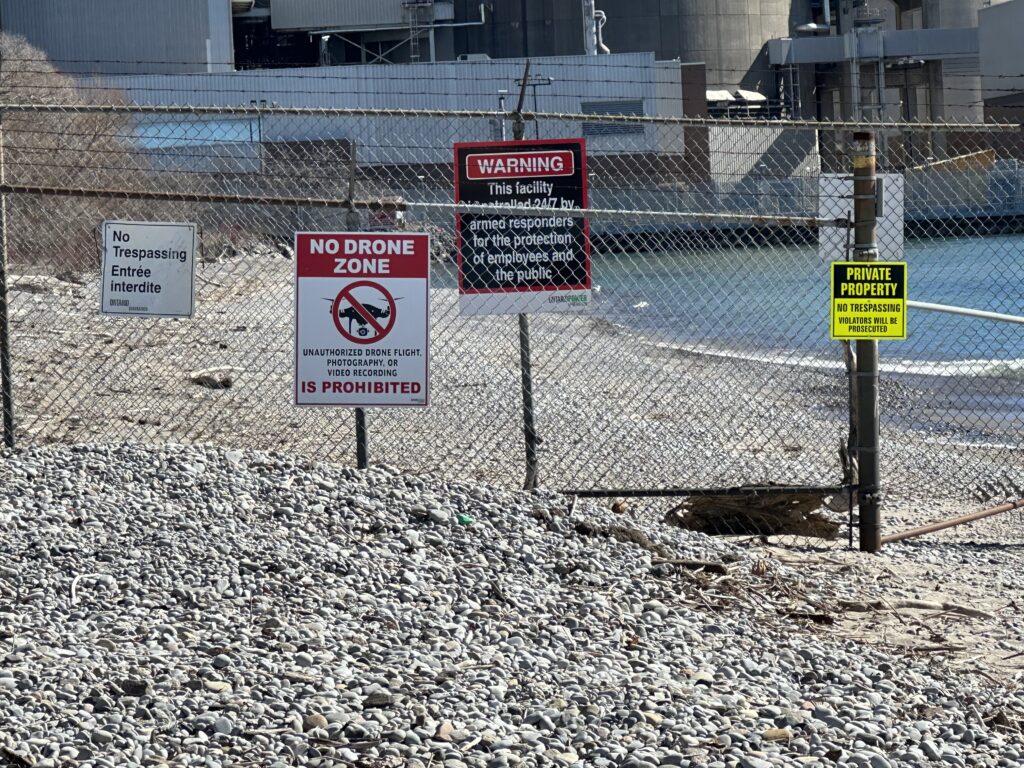

The trail is lined with trees, tall grass and a variety of sun-faded OPG-branded informational signs. One states that over 5,000 trees were planted along this path. Their sturdy trunks and woven branches are almost enough to completely obscure the view of the plant. Still, the chain link fence, topped with barbed wire, with occasional signs warning that the area is constantly patrolled, serves as a reminder something is lurking behind the thicket.

“We had that one alarm four years ago,” Bolton said. “I heard this alarm and went ‘Oh, that must be a mistake.” It was. In 2020, an emergency alert was sent in error. Most of Ontario received a blaring alarm at 7:23 am on Sunday morning. It warned of a vague incident and stated that there was no abnormal release of radiation. It took 43 minutes for the error to be publicly corrected.

Not all incidents have been mistakes. In 1994, a pipe burst led to a temporary shutdown of unit two. A meltdown was prevented through the activation of emergency systems. This is considered among the worst Canadian nuclear disasters, though no one was harmed or injured and no abnormal radiation was released.

In 1983, a fracture was found along a pressure tube, causing a leak of heavy water – a type of water that has a slightly different chemical makeup, making it quite literally heavier than regular water. Heavy water was also accidentally released into Lake Ontario in 1992 and 1996. Units one through four were shut down soon after, partially due to safety concerns, though two of the units would later be restarted.

When asked if residents are nervous about its presence, Mayor Ashe said newcomers might express concern, but it usually fades. “Long term, they just don’t have the same angst.”

Bolton agreed. “It’s accepted. Anyone who comes in here or lives here or works here, it just is,” she said.

“We do have radiation pills that are sent out,” Ashe said. “We’ve never had an incident where we had to use them, but it’s better to plan.” Radiation pills are also known as iodine tablets. Taking one, should it be needed, prevents radioactive iodine from being absorbed, reducing the risk of cancer. Basically, it overloads the thyroid with iodine to the point that no more – whether radioactive or not – can be taken in.

Receiving them can be a shock. “When you get these little boxes of iodine, and get the instructions in case of emergency and all of that. It’s just a little wake-up kind of thing,” said Bolton. All residents within 10 kilometres of any nuclear station are encouraged to have these tablets in their homes. They’re free for anyone within 50 kilometres of a plant.

For most who live in Pickering, it’s easy enough to toss the pills in a drawer and forget any notion of existential threat. The concrete plant may stick out along the shore, but there are plenty of places in town where it’s out of sight, or hidden behind purposefully planted trees. Standing on Bolton’s porch and facing south, Liverpool Rd. offers a reactor-free peek of the waterfront. Inside the café, she explains the nuclear plant isn’t feared. It is a part of life, but she doesn’t dwell on it. “I think ignorance is bliss.”