By Eduard Tatomir

The parking lot fills as families arrive; parents hold their children’s gloved hands as they dash for the one storey, orange-bricked building. They may be a few minutes late to the Sunday service, but most of their eagerness comes from escaping the cold.

It is a haven to dozens of families from many backgrounds and it is open to everyone. Feb. 23, 2020. (Eduard Tatomir/T•)

Just a stone’s throw from York Mills subway station, in a quaint, tucked-away neighbourhood sits the Agricola Finnish Lutheran Church. The area is placid with its greenery and open space. Next door to a park with a free-flowing pond and surrounded by eggshell-white, affluent homes, this place of worship keeps its antique charm and unsophisticated, rustic roots intact.

Visitors trudge through the snow and are welcomed inside. Oftentimes there will only be silence or perhaps the sound of the pastor giving a sermon. From time to time, the heavenly choir will be singing at the front near the altar. Warm candle lighting and the polished wood pews make it feel like a second home.

That is, if you can enter the space at all. If it’s not a Sunday morning, the front doors likely will be locked.

Hannele Väättanen has been a member of the church for many years. The congregation may be shrinking, but the community is still strong, she says. On March 9, 2020. (Eduard Tatomir/T•)

There’s a sparse crowd for the English service on this Sunday. The English congregation takes over the church following the Finnish service. On March 1, 2020. (Eduard Tatomir/T•)

“That’s because the building is usually rented out throughout the week,” says Hannele Väättanen as she stands against the doorframe leading to the empty chapel. It’s a weekday and she’s only there to fill out some paperwork, organize some files and keep the space tidy. “Our congregation has gotten smaller and smaller so we do rent to survive, to cover the costs. We rent the parking, we rent the space. It’s not ours anymore.”

Väättanen has been the secretary and a member of the congregation for the past two years. The church is the only thing that’s kept her in this country after she and her family immigrated here because it’s given her a job and a sense of community. She has seen new faces come and old faces go but still, she maintains that the community remains strong, even if it may be diminishing.

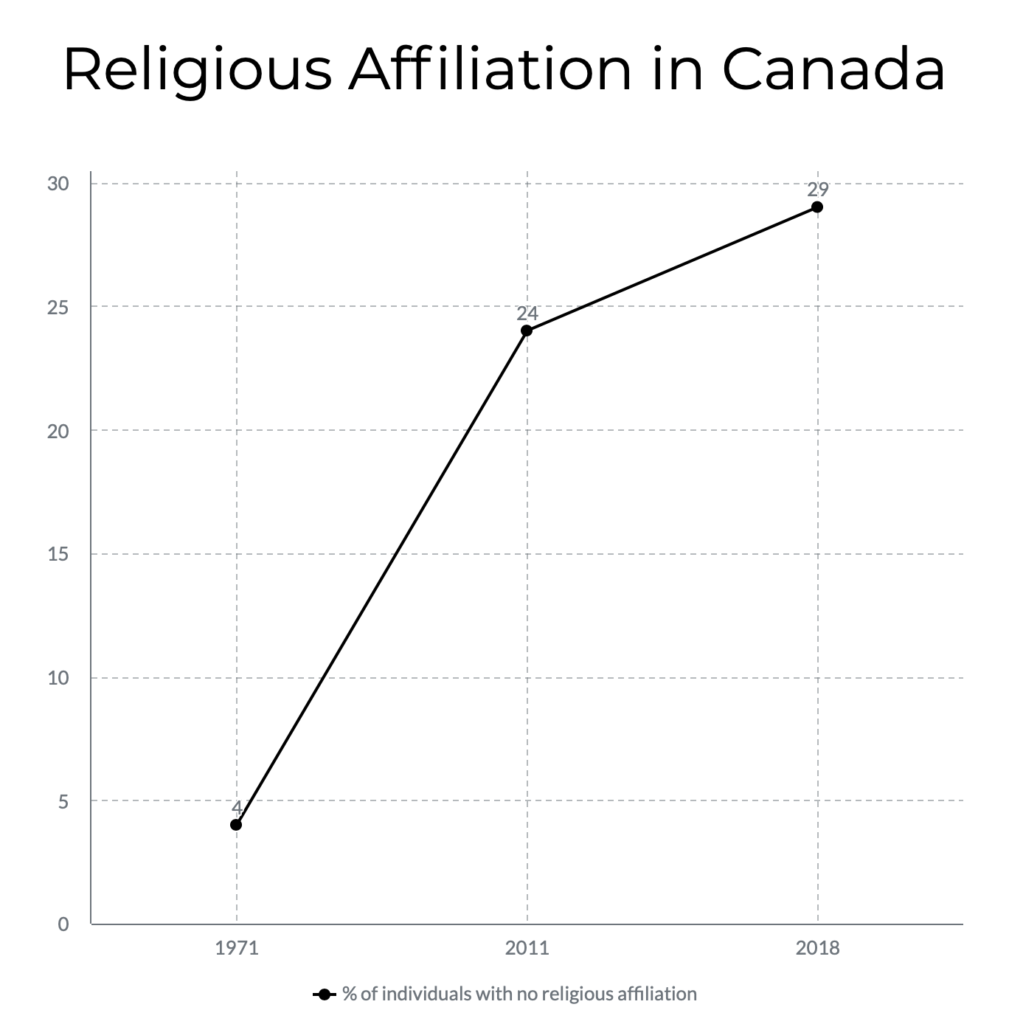

Religious affiliation and church attendance among Canadians has fallen over the last few decades. Canadian census data indicates the number of people claiming to have no religious affiliation has risen from 4 per cent in 1971 to 24 per cent in 2011. It grew to 29 per cent in 2018, according to the Pew Research Center. For many Canadians, churches and organized religion have increasingly lost their appeal over the years.

This could spell trouble for the future of church communities and congregations.

As Väättanen cleans the pews of the church and straightens the Bibles behind each seatback, she notices a man at the door. Elias Koskinen. He looks worn out, his jacket falling off his shoulders. Her face lights up as she goes in for a hug.

“How’s your mother doing?” He sighs. “She’s resting, but doing better,” he says. They are more than just acquaintances from Sunday worship. They are friends.

Service every Sunday is held in four different languages — Finnish, English, Swedish and Estonian — to accommodate a wide range of communities. After they pray, everyone is welcome downstairs to feast on soup, sandwiches and coffee. People can drop spare change and small bills in a bowl at the end of the table to show their appreciation. It’s always filled with cash.

The church hosts four Sunday services each week, in Finnish, English, Swedish and Estonian. On Feb. 7, 2020. (Eduard Tatomir/T•)

Kids run around, playing tag while the adults sit at a last-supper style table discussing work, imminent errands and their qualms about technology these days. A larger church would look at this gathering and call it a slow week but this is their most impressive crowd in a while with nearly 40 people breaking bread.

The room smells of pastries and is bursting with conversation. Whenever someone walks past, they feel welcome enough to butt in and join the chatter. Soon, everyone has an empty plate and a finished cup of joe as they leave to start their days.

The church tries to be as accommodating as possible and the pastor asks people to stand during the service “as you are able.” (Eduard Tatomir/T•)

Hilkka Luus, the chair and counsel of the church, arrives last to the meal as everyone is finishing and heading out. She was working upstairs, making sure everything was prim and proper for the English service. She is more than happy to put the needs of the church and the people before her own.

“Some of the people who were originally here when I started to come in about 1980 are no longer with us, but there are some new faces now and new faces coming all the time. But we used to be bigger.” In fact, it’s the smaller size that lets her feel so close to everyone.

“It has grown in a sense that there are fewer Finnish families moving to Canada and the older section is getting smaller but there are still new families and individuals that come for a year, two years, or stay for longer. Some aren’t even Finnish. The point is to make sure that everyone feels welcome.” And she does. Everyone knows everyone and she considers that a blessing.

The choir is a beloved part of Sunday services and essential to their congregation. On Feb. 23, 2020. (Eduard Tatomir/T•)

Another woman sits at the table and quietly eats her food. She has soft eyes and a persistent smile. Elizabeth Virtanen has been attending the church for decades now. She has no children and her husband, Tauno, died in 2012.

“These people have known me for so long. They feel like more than my friends. I know their children, they know me and I feel like I belong.”

She recalls walking the church a few weeks ago when one of the kids came up and hugged her. “She was my friend’s daughter and I wasn’t expecting that. I almost wanted to cry.”

Pastor Matti Kormano prepares his short sermon for the English congregation. Oftentimes, he won’t need his papers to remember what he has to say. On March 1, 2020. (Eduard Tatomir/T•)

Everyone rises in prayer just before communion is given out. After this final phase of the service, members either head home after saying their goodbyes or go downstairs to eat and chat. On March 1, 2020. (Eduard Tatomir/T•)

If Pastor Matti Kormano isn’t preparing his sermon for the English or Finnish service, he is likely mingling with the men and women he just gave communion to earlier. He will grab a seat along with the guests and drink a cup of coffee while they all feast.

Kormano can attest to the smaller congregation size, but isn’t complaining. “It’s not as big as it once was and the children aren’t very involved, but I trust they will be in the future. Hopefully.” He laughs, but during the service, groups of five to seven kids sit near the staircase on their phones.

Some of them leave again right after and meet up with their parents after the service. On March 1, 2020. (Eduard Tatomir/T•)

This doesn’t concern him much because he is able to look around and confidently remember each face and almost each name week-to-week. As the children grow into their teens, they may start to attend less, but Kormano says they “usually always” come around, even if statistics claim otherwise.

“We may not be a large congregation and renting the space is necessary to survive, but I’d prefer a handful of loyal members over a room full of people who change every week.”

A week later when everyone gathers together for another Sunday service, they greet each other with nods and smiles before taking their customary seats. When they close their eyes in prayer and their kids leave to play downstairs, they can trust that everything will be OK in a space that feels like their home away from home.