By Jennifer Nguyen

For Hanoians on Nguyễn Hữu Huân Street these early February days, it’s a common sight to find people sitting next to people outside an alley tucked away from bulkier storefronts, chatting over paper cups that fit just right in their palm and are filled almost to the brim with a thick golden foam. A sweet aroma fills the air, growing stronger as one travels further down the passageway.

“Welcome to Café Giảng. Only take-outs for now, please and sorry!”

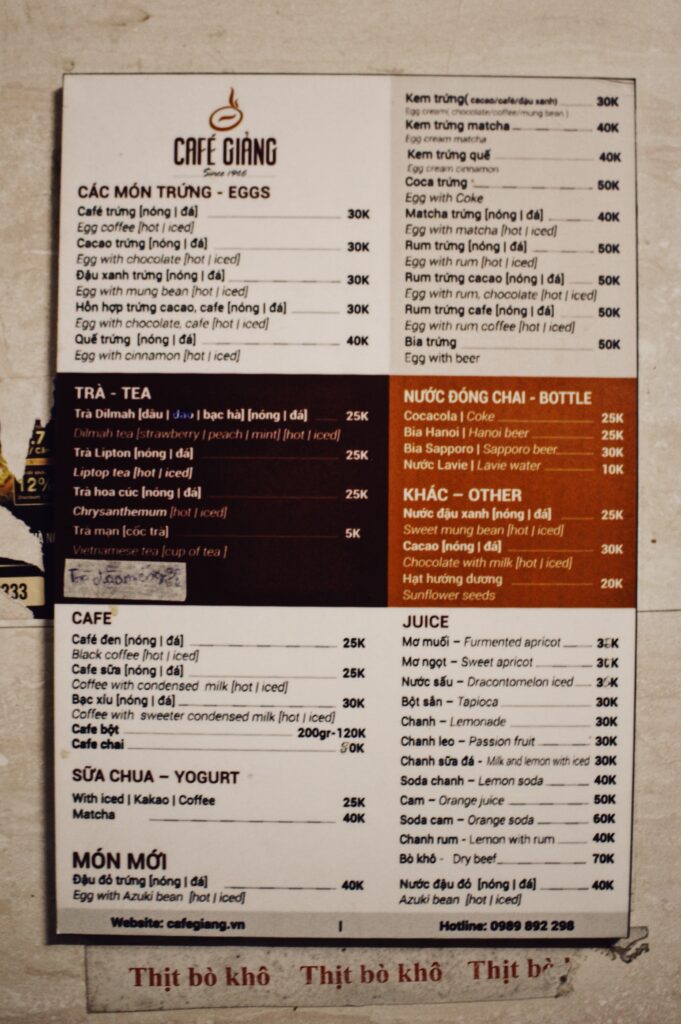

Nguyễn Trí Hòa, the owner, paces forward from the cashier booth at the back in a matching denim vest and newsboy cap ensemble, extending a weathered paper copy of the menu. The first line reads in bold “egg coffee, hot/iced” next to a price tag of 30,000 dong, or $1.60.

At the age of 65, Hòa sports a remarkable shoulder-length, salt-and-pepper mane. The Vietnamese traditionally associate long hairdos in men, a defiance of norms, with the artist community and their yearning for freedom of expression. And Hòa lives up to that, as a natural-born in the art of coffee.

Café Giảng’s many signboards above and to the right of a “take-away only” announcement, at the entrance of Lane 39 Nguyễn Hữu Huân Street, Hanoi, Vietnam. Photographed on Feb. 18, 2021. (Jennifer Nguyen/T•)

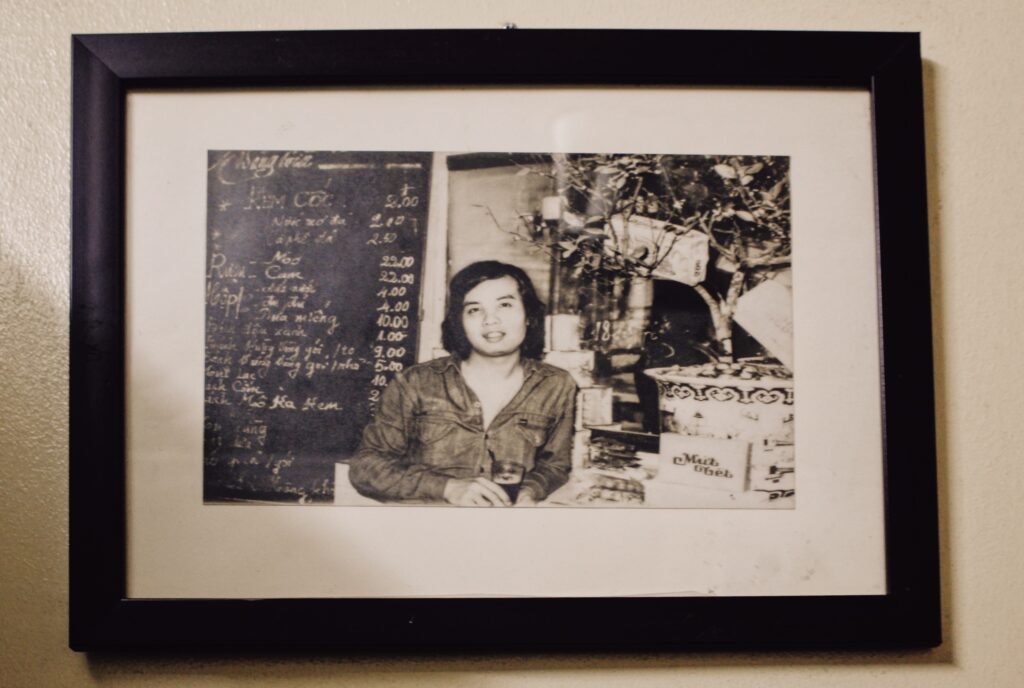

The location’s owner, Nguyễn Trí Hòa. (Jennifer Nguyen/T•)

Café Giảng’s bilingual menu pinned on the wall. (Jennifer Nguyen/T•)

Nearly a century ago in the 1940s, when Vietnam was still under French colonial rule, Hòa’s father Nguyễn Văn Giảng was working as a barista at the capital city’s first five-star hotel, the Sofitel Metropole Hanoi. Here he mastered the craft of making a fancy Italian cappuccino.

But there wasn’t a way to serve this drink beyond the rich man’s world. Outside of the Metropole’s glass windows and beaming halls, Hanoi was a battlefield deep in poverty.

“Milk was a luxury then and yet you need about 200ml of it for a dozen cups of cappuccino. But if you take eggs instead, which could also be whipped into a froth and was accessible to every household — since we all raised chicken, you can make something 95 per cent similar while 10 times cheaper,” Hòa said. “So my dad thought ‘why not?’”

Giảng soon left his hotel job to invest in his new invention, but this period up until the 1970s wasn’t a fruitful time to do such business in Hanoi. Since coffee wasn’t in the rigid communist economy’s favour — let alone egg coffee — Giảng selling it was the equivalent of being a drug dealer, Hòa said. On the surface, they seemed no more than just another unassuming tiny tea stall by the road. But if you were in the know, then Giảng always had a real treat waiting. All one had to do was ask.

(Translation: Back in the days of the war – and I’m sorry to say this – but selling coffee was like selling contrabands. The police would pay you a visit right away. And they would strip away your property papers and food stamps for the violation, which means the whole family would have to starve. So of course we were very scared. It was like playing a game of hide and seek, because we knew we weren’t allowed to do such business but yet we were depending on it. We only got to open and operate properly after Independence Day and the economy became more relaxed. But Hanoi didn’t have the prevalent coffee culture it does today, yet. Mostly only artists drank coffee, while the working class preferred a cup of tea. Then [after the Americans left the south of Vietnam and there was unification] since 1975, the Saigonese ways of life reached us. That’s when people got used to the concept of “morning coffee.” That’s how it all changed.)

From a few stools by the sidewalk that were convenient enough to clean up whenever the authority patrolled, Giảng and his family moved on to open their first store, then second, soon establishing a name for themselves in the city’s beverage scene.

The concoction prospered with time into a made-in-Hanoi trademark. Exquisite palates in the city, across the country and internationally proclaim that Café Giảng is the place to be for anyone who wants to try an authentic Vietnamese egg coffee — cà phê trứng.

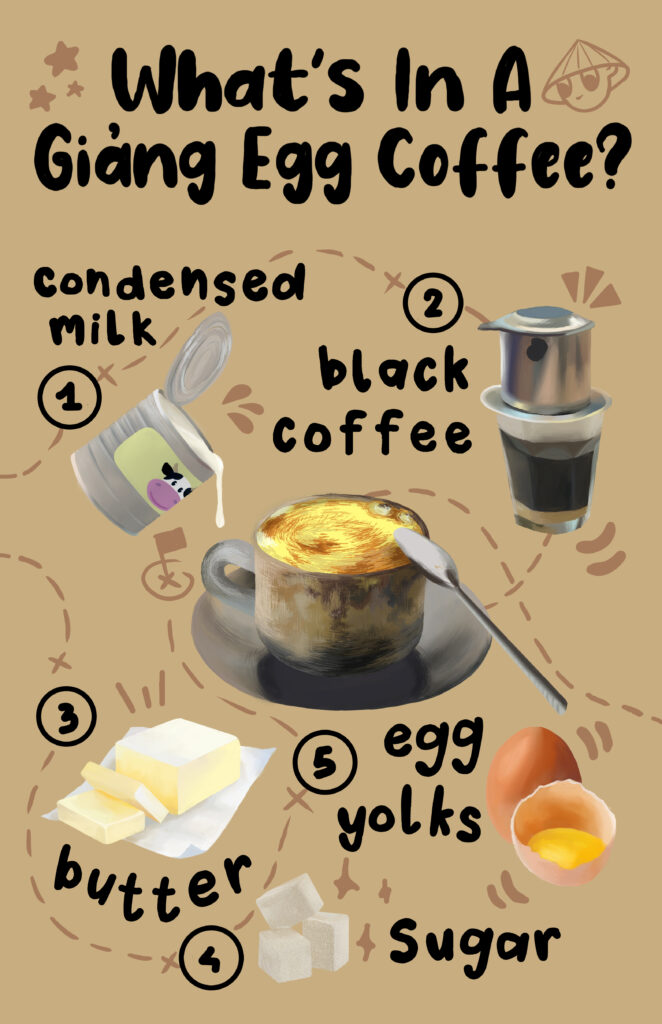

Start with some piping hot home-brewed black coffee in a cup, though you can add ice if desired. (Jennifer Nguyen/T•)

Then whip up the egg mixture, the components of which are most certainly best kept a family secret… or are they not? (Jennifer Nguyen/T•)

Once the golden foam achieves the right consistency, lay it onto the coffee bed underneath. Enjoy the intertwining layers of contrasting flavours. (Jennifer Nguyen/T•)

“Don’t like bitter? I’ll only put a few drops, how’s that?”

Hòa calls out from the dimly lit kitchen, insisting that a first-time customer has a taste of his assorted blends in her egg cocoa order. In an effort to get with the times, he’s incorporated in his menu more modern, global trends, such as cocoa, matcha, cinnamon and rum with eggs. Still, when given the choice himself, Hòa almost always goes for the original concoction — a drink so creamy it is borderline dessert; a bittersweet entanglement of tastes.

Like his seven older siblings, Hòa grew up helping out at the family store. While another two of them also went on to have their own Café Giảng branches, Hòa takes pride in being the only one to take the “proper” route of going to culinary school for bartending and landing a job at a state-run food and beverage company, where he met his wife, a chef.

The couple left to open their café shortly after their father passed away in the late 1980s. Taking up the majority of space on their walls are pictures of the early days, when Giảng was still in the business.

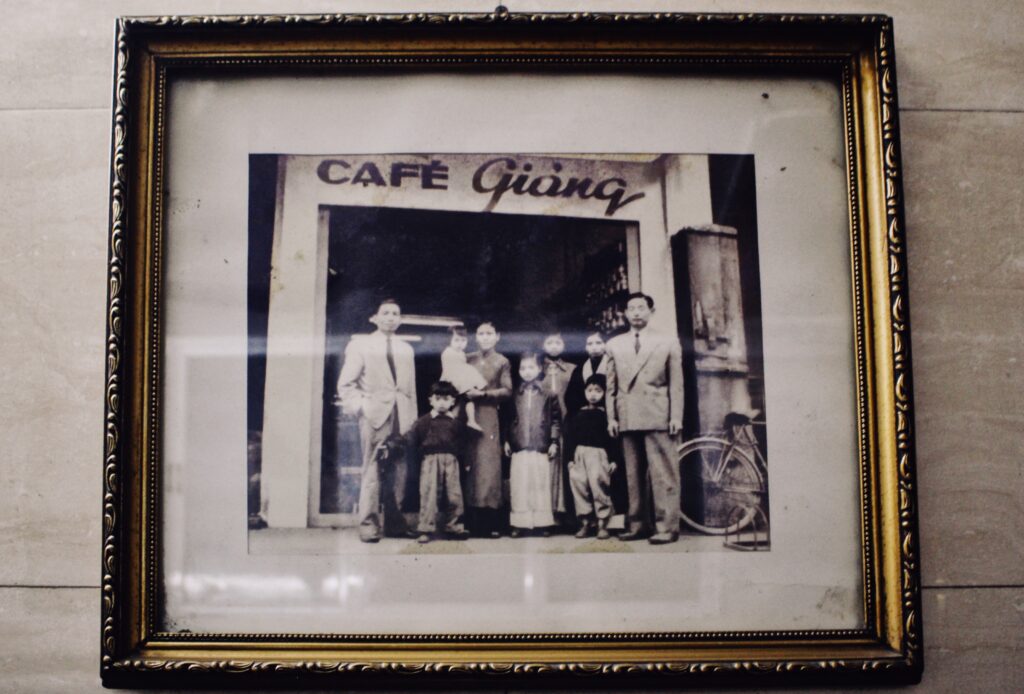

“My father isn’t in this one… That’s my mother in the middle,” Hòa points. “I wasn’t born yet, but here’s Đạo and next to him Bích.”

Giảng and his family in front of their first store at 90 Cầu Gỗ Street. (Jennifer Nguyen/T•)

Six of Giảng’s children photographed with their mother, his wife. On the far left is Hòa’s oldest brother Đạo, next to his big sister Bích. (Jennifer Nguyen/T•)

Hòa’s 75-year-old brother Nguyễn Văn Đạo owns the family location on bustling Yên Phụ Street. While Đạo previously worked in engineering, he is no less of a coffee expert. His rendition of the egg coffee holds the reputation of coming closest to Giảng’s original flavour, according to those who had the chance to try both. For Hanoi’s older generations, this more intimate Café Giảng, where the owner knows his regulars’ orders by heart, offers the comforts of days gone by.

Fewer may know of a third Café Giảng opened by Hòa’s oldest sister, the late Madam Bích, for it doesn’t bear her father’s name. While the two brothers were adamant about family branding, Bích added her own spice to the mix and named her place after herself: Café Bích, although later changing it to Café Đinh to reflect the location on Đinh Tiên Hoàng Street. As a former high school literature teacher, she nurtured an inseparable bond with Hanoi’s youths. College art majors loved coming here to find Bích playing Pink Floyd in the background — she was and is dearly remembered as an avid fan of Western rock.

Though situated inside a tiny alley, Hòa’s café is nowhere small in scale. The two-storey establishment is dubbed the family chain’s unofficial flagship store, particularly popular with foreign tourists to Hanoi, who made up the majority of Hòa’s customer demographic before COVID-19 travel restrictions were imposed.

A section on the first floor of Café Giảng on Nguyễn Hữu Huân. (Jennifer Nguyen/T•)

A section on the second floor of Café Giảng on Nguyễn Hữu Huân. (Jennifer Nguyen/T•)

Hòa’s not too fond of national expansion — he has turned down numerous franchising offers across Vietnam — though it’s his passion to bring the egg coffee to the world. In 2017, Hòa took his first step towards the dream in collaboration with a Japanese partner to open Café Giảng in Yokohama, Kanagawa. His next stop? “Hopefully the United States.”

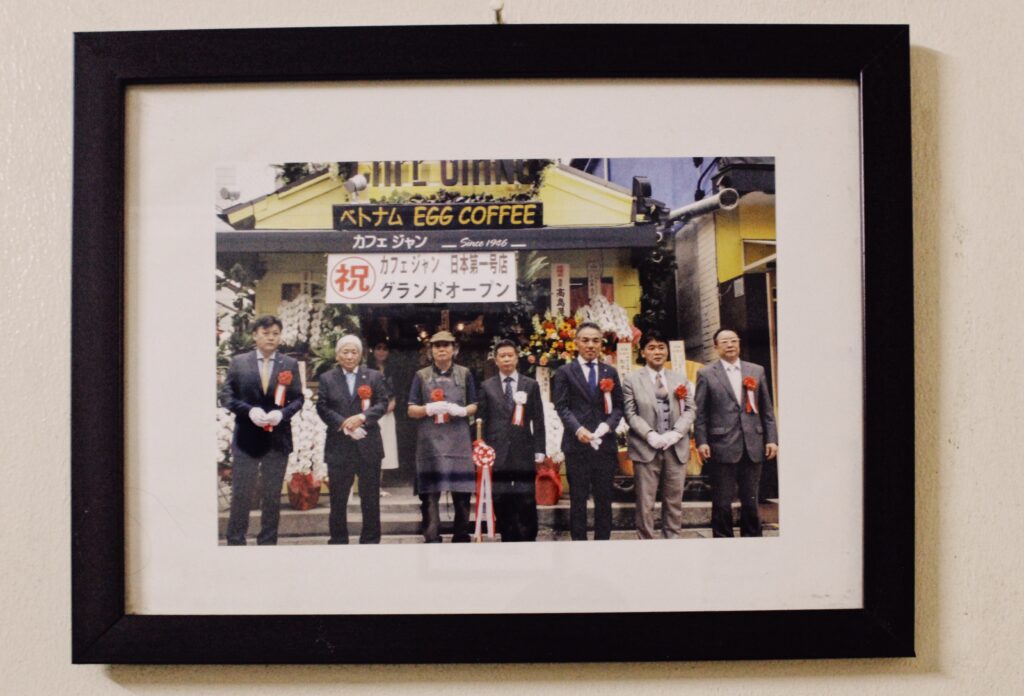

A poster for the grand opening of Café Giảng Yokohama on the wall of Café Giảng Nguyễn Hữu Huân. (Jennifer Nguyen/T•)

Hòa, third from the left in an apron, joined his business partners in Japan on their 2017 opening day. (Jennifer Nguyen/T•)

Apricot blossom petals scatter on the brick floor tiles. It’s springtime in Hanoi, or Café Giảng’s peak season in a pre-pandemic period, as people gather in celebration of the Lunar New Year over a cup of egg coffee, its flavour as rich as the capital city’s history. In the absence of patrons’ chatters, the tireless grinding of an egg mixer is the only sound echoing the decades-old coffeehouse. Hòa gazes out to the entrance, following the footsteps of the now-departing first-time customer with an egg cocoa. Perhaps he has fond memories of busier days on his mind.